by David Chadwick

Redone version posted 2-10-14. Originally written quickly in March 2012 for the book Remembering Kobun published by his disciple Vanja Palmers. I got it in at the last moment with links and notes. Then when they sent me their edited version I didn't look at it which was a thoughtless mistake. I didn't even notice it called Clay my younger brother instead of younger son. I'd called him Clay the younger. Don't know why didn't put more time into it then. Sent this version this morning to Vanja for next edition with apologies for having been so discombobulated. - dc

While looking through Grahame Petchey’s photo album of the great root monastery, Eiheiji, he pointed out Kobun Chino as a monk assigned to watch over him. It's interesting to hear Grahame talk about Kobun back then in the early sixties because it's not the Kobun we knew in the States. Grahame says Kobun rode him and Phillip Wilson hard, would chastise them for the tiniest infractions. Grahame says Kobun was "the perfect monk, the epitome of Japanese militaristic Zen." Wow. Not at all so here in the States. I guess our hippy magic worked on him like it seems to have on Shunryu Suzuki whose children described him as strict, severe and distant.

I first saw Kobun at the top of the stone steps by the big old oak tree when he arrived at Tassajara in June, 1967 - wide eyed, eager, and in a new element. Bob Halpern and I showed him around and pestered him till late at night asking him about everything we could think of from zazen to a monk’s diet. He had a yellow robe so we thought he must be completely enlightened. When? Where? What was it like? He told us of sitting alone reading poetry then walking in the moonglow in his master’s garden and disappearing into a subtle light.

Kobun was a wonderful addition to our fledgling Soto Zen Buddhist monastery. His English was pretty good from the start. He taught us a lot quickly and language wasn’t a problem. He fine-tuned the services, was an exemplar of how to chant, hit the bells, and use the Oryoki bowls and cloths for formal meals in the zendo. He taught us a great deal about what the words meant – of the chants, objects, monastic positions. He trained us in form yet was informal and asked us to call him just Kobun.

Kobun Chino and Shunryu Suzuki‘s cabins were the only two at Tassajara with tatami mats. I hardly knew how to use a saw, but with Paul Discoe as an advisor, I quickly made each of them a low desk to use while sitting on the floor. Kobun was most grateful and offered a sumi painting in return. I expected him to create it on the table but he did it on the tatami which he protected with newspaper. He kept going till finally one was selected. A year before I’d been a stoned hippie in the Haight and now I was sitting in a Zen monk’s cabin drinking the special green tea he’d brought from Japan as he hypnotized me with a brush. I showed him my penmanship, a letter I’d written my sister. He said if he sent something that messy to his brother, it would go unread into the waste basket. Later I would spend many hours studying the kanji in our chants and he was always available to explain the shades of meaning.

Kobun liked to work in the kitchen. He taught us how to make traditional Japanese daikon pickles and pickled cabbage. I found it curious he thought white noodles were healthy. Driving him in from town he asked me to stop near the top of Chew’s Ridge so he could pick ferns to cook for a unique day off dinner side dish. He gathered mushrooms from the woods and prepared them as his mother had. They were sumptuous though some of us were nervous that he might be poisoning us.

He brought with him a bit of magic and animism from the old country. He talked of spirits and when we laughed he asked then why were we afraid to walk in a graveyard? Driving him out of Tassajara he had me stop to move a dead rabbit off the road. He gently placed it on an embankment, covered it with leaves, and said, "Or else he cannot become Buddha."

He extolled the virtues of an occasional cigarette which gave me the opportunity to join him. Soon after his arrival in the city at the kitchen table with Suzuki, Bob Halpern pulled out a pack of Camel non filters and offered one to Kobun who accepted till Suzuki raised his hand and said, "No, Chino Sensei doesn’t smoke."

He liked to go for hikes in the woods in his samue, monk’s work clothes. He inspected a raspy tubed grass and said it was akin to a plant used in ancient Japan as sandpaper. I taught him to keep an eye out for poison oak and warned of rattlesnakes, showed him how to chew a bit of a small top yerba santa leaf for the sweetness and calm feeling, showed him a century plant bloom rising into the sky. Bob and I took him down creek to the narrows. He sat on the side as we showed off diving and jumping into the pool. We ignored his pleas leaping off the side of the cliff from a high point, barely clearing the granite ledge below.

I drove him to Monterey for day trips, to and from San Francisco, and would spend as much time as possible introducing him to friends, beaches, restaurants, and sights along the way. Peter Sellers in "The Party" brought us to tears laughing. He kept slapping my thigh to share his delight. Got him in six hours later than expected at Tassajara and the head monk said he felt sometime he couldn’t trust me. I said, "That’s okay, Kobun can." Kobun found everyone and everything in his host land fascinating and when out of the monastery would accept a drink and, in time, a hit off a joint. I couldn’t get him to wear a seat belt till one day I had to slam on the brakes on the freeway smashing him into the dashboard. He quickly buckled up after that.

He was patient and understanding of our foolishness. Serving soup in the zendo one lunch in the first practice period, there were so many people we had to fill the four large steaming tureens to the top. Suzuki and Kobun were served first. Holding the heavy pot high, I walked down the aisle, clumsily placing it before Kobun with a thump as a tidal wave of sizzling soup sloshed out into his lap, drenching his sacred okesa and surely burning his body under the cloth. He didn’t flinch. After the meal I ran to his room to apologize and offer to clean his robes. He let me follow him to the creek. He had taken his kimono and koromo apart and washed them and his tablecloth-shaped okesa in the gently flowing water. They were dry in a hot summer hour and he sewed them back together with long running stitches.

Sometimes he’d get exasperated with me. I had been insisting that I speak directly with guest teacher Tatsugami who'd told Kobun to correct me about how to get up from sitting in seiza. "You have no mind for teaching!" he finally yelled at me when I wouldn’t listen to him. That hit me so heavy I went off and cried.

He spoke very slowly, with pauses between his words at times, especially in lectures. His voice tended to tremble. I suggested to Wako Kato, an early Sokoji priest, that maybe Kobun’s halting speech had something to do with him wanting to make sure his English was correct. Kato said, "No, he speaks Japanese the same. It makes me want to beat him up." Like all the Japanese priests, Kobun would sleep in zazen. But he loved his private time and his cabin light would shine so late he’d be exceptionally sleepy the next day. Once during the guest season, as he gave a lecture to students and a number of guests sitting in chairs, he spoke slowly, softly, long spaces between words, then a longer space till his head dropped and in a moment drool slid from his open mouth finally waking him up when it landed in his mudra. He composed himself and continued the lecture.

At first Kobun had no defenses against exotic temptations he’d never experienced, at least not without the pressures and limitations of his home culture. One student who was away during a winter break, was shocked to see his own wife answer the door to Kobun’s cabin when he came to pay his respects upon returning. He quickly sized up the situation, scooped her up, drove to the city, and went straight to Suzuki. The times were incredibly permissive. The husband didn’t hold it against him. Nonetheless I could see for a while how bad Kobun felt about it. Being from another culture he couldn’t necessarily tell if people were mentally stable or not. He had a brief encounter with an older woman. Soon after that she entered the zendo nude during noon service, walked right by us who were standing chanting. When the service was over she stepped up on the altar, sat on a zafu in the center, and started giving a lecture until she was gently asked to stop and escorted out.

That was the beginning of a period when Kobun refused to leave his cabin. It went on for a long time, over a month as I recall. I’d go talk to him. He’d stay in his sleeping bag and barely respond at all. I suggested we take him to a doctor. He replied, "No doctor can treat this illness. I am the victim of evil desire." One day while carrying the stick, I walked out of the zendo to Kobun’s cabin and knocked. Kobun opened the door. I gently tapped him on the shoulder. He gashoed with me and I returned to the zendo. Kobun agreed to go to the baths with Suzuki. A Volkswagen was driven up the path to near their cabins. They both got in and were chauffeured to the bridge to the baths. Later they were driven back. Finally, one day, Kobun got up, went to the zendo and the era of the cabin hermit was over.

Kobun didn’t seek after rule breaking in the monastery. It would come to him. Alan Marlow offered him a hash brownie a friend of his had brought in. He didn’t tell Kobun what was in it till it was too late. In the city a woman turned him on to LSD which he later called spiritual masturbation.

I remember when Yasutani, Soen Nakagawa, and other luminaries were visiting Tassajara in 1968. Kobun stood next to me looking at them. He commented that Yasutani, even though he was Soto, was a good example of a great Rinzai Roshi and Suzuki of a great Soto Roshi. I asked what about Soen and he said, "Too much personality."

Kobun and Harriet fell in love and wanted Suzuki to marry them. The wedding was planned for July. Harriet says they went to Tassajara to see Suzuki about their wedding, that Kobun and Suzuki spoke in Japanese and Kobun told her that Suzuki had decided not to perform their wedding ceremony. She says that came as a total shock to her. They left Tassajara and got married in the Santa Clara courthouse with Les and Mary Kaye as witnesses.

My understanding back then was that Kobun’s father was abbot of a large temple on the West side of Japan. I heard back that he did not approve of the upcoming marriage. I remember when they came to Tassajara to talk to Suzuki about their wedding which had been planned for July. There was a tension in the air. Suzuki’s wife asked me where Harriet was staying and I told her to mind her own business. I also remember asking her why on earth her husband would honor Kobun's father's wishes over Kobun and Harriet's. Kobun and Harriet came out of Suzuki’s cabin distraught. Harriet was sobbing. As I recall, I suggested they leave, go to a motel, and find a justice of the peace and that I carried Harriet to the car she was crying so hard.

Later I’d go visit Kobun and Harriet in Los Altos. People from Zen Center and other Suzuki lineage groups came and asked him for favors that he’d always grant – help with ceremonies and translations and writing kanji on rakusu, the bibs of ordination, usually without any compensation or donation as would be customary in Japan. She had a reputation for giving his guests a hard time. I thought for one that she got fed up with the way they'd be so overly respectful with him and ignore her. I never had that problem because I enjoyed visiting with Harriet and her mother. I’d walk in, say hi to Kobun as I walked by, and then visit with Harriet and often her and her mother together. Harriet had not it seemed to me forgiven Suzuki. I enjoyed the way they’d put down Suzuki whom her mother once called, "That nasty little man." I didn’t get to hear opinions like that anywhere else and I sympathized to a degree, at least in terms of how he'd dealt with their wedding plans. I’d get lost in the conversation with them and forget Kobun till she’d suggest maybe I should go visit with him. I'd just visit a little and leave him alone which is what I thought he really enjoyed.

After Harriet, Kobun lived with Stephanie for some years, much of it in Steve Job's 17,000 square foot Spanish Colonial style house in Woodside not far from Los Altos. She told me Kobun devastated her when he announced at the dinner table at Jobs’ place that he had a new love. Kobun introduced me to Katrin, his new young German wife-to-be, at Maezumi’s funeral in LA in 1995. He was smitten. She was smiling - and pregnant. His prior mate was there too. "Children never came to us," he said to her.

Steve Jobs had been sitting at the Los Altos zendo and had taken on Kobun as a teacher. He gave Kobun a place to live on his estate. Kobun brought him to Tassajara one day in the 1990s. Rick Levine remembers them driving up in a big SUV. Brit Pyland recalls Kobun showing Jobs around too that day. It would be just like Kobun to come in without calling and surely everyone was happy to see him and likely didn't know whom he was with. Jobs never practiced or did retreats there as I've read in several places, or at least I've not heard that he did from anyone.

Kobun performed a marriage ceremony for Jobs and his fiancÚ Laurene Powell in 1991 at Yosemite.

Through the years. I’d look Kobun up in Arroyo Seco or Los Altos or Santa Cruz or see him at the San Francisco Zen Center’s City Center or Green Gulch Farm Farm where his expertise would be called on from time to time. He moved around a bit - sometimes without telling his students.

Bob Watkins had been work leader at the first practice period at Tassajara. Later he was ordained by Kobun and his home in Arroyo Seco above Taos became the groups’ zendo. He gave Kobun a great deal of financial support through the years even though he didn’t have a lot to spare.

Bob Watkins said he once called Steve Jobs asking for some financial help for Kobun and that Jobs had said he’d only give Kobun money if he came back to live there. Bob asked Kobun why hadn’t he ever asked Jobs for money and he said it had never occurred to him. [Steve Jobs cuke page] Bob told me that in 1993. In 2019, Richard Baker told me Kobun once gave him the same answer to the same question. It could be that the three of them were together at that time.

Bob, Kobun and I walked to the site for a home for Kobun in the pine woods beyond the Arroyo Seco zendo. I wonder if it ever got beyond the foundation we admired. Bob told me, "Kobun gave everyone the medicine they required - it was person specific. You had to be careful not to take another persons’. The teaching for me was to hang with Kobun and Suzuki."

I took Kobun to Ken and Treya Wilber’s home in Marin County. They’d mentioned several times they wanted to meet him. I’d stupidly bought a fifth of vodka and Kobun who wasn’t much of a drinker got pretty drunk there. When we said goodbye he demanded he drive and I refused. He insisted. I said no. He hauled back and slapped me in the face. I shook my head no. Ken and Treya stood and watched as Kobun slapped me hard a few more times. Finally I picked him up, walked him over to the other side, and put him in the passenger seat. Then I took him to the home of an outrageous lover of mine who found him delightful. As we left she whispered in my ear, "He’s a biter." After that we went to an all night diner for French toast and coffee. He wanted us to fly immediately to Japan. It was hard to convince him that wasn’t possible at the moment. Police at another table eyed us suspiciously.

Kobun introduced me as a "very evil monk" in Arroyo Seco. It was February of 1986 and my mate Elin and I had dropped by without calling which wasn’t always useful anyway. It was the last hours of a seven day sesshin which he ended on the spot when we arrived. Elin, Kobun, Alan Marlowe, and I then went out to a balcony and smoked a joint. Alan was coming on to everyone there regardless of gender and I asked him if he was being careful in light of the recent death by AIDS of his boyfriend. He said his attainment was so great he could neither get nor pass on AIDS. Several years later, as Alan lay dying from AIDS and cancer in Kobun’s arms, his memorable last words were, "The udumbara taxi has arrived."

Tozen Akiyama came from Japan to be a priest in America. Kobun had agreed to be his sponsor and was to pick him up at the airport. He didn’t nor did he respond to any of Tozen’s attempts to contact him. Finally when it was too late, Tozen met him somewhere. Kobun apologized. Tozen asked him again if he would be his sponsor upon his return. Kobun said yes and details were quickly agreed on. When the time came Kobun didn’t show and couldn’t be located. Tozen found another sponsor. But he still remembers Kobun fondly.

Kobun lived with Stephanie for some years. Stephanie told me Kobun devastated her when he announced at the dinner table at Jobs’ place that he had a new love. Kobun introduced me to Katrin, his new young German wife, at Maezumi’s funeral in LA in 1995. He was smitten. She was smiling.

Kobun was a big hit at some of the events around Richard Baker and Marie-Louise von Baden's wedding in 1999. His disciple Vanja Palmer brought him from Lucerne to Schloss Salem in Germany. Baker insisted Kobun not wear robes to the wedding. Kobun said he didn’t have anything else to wear. He and Vanja skipped the wedding. They came to a later event. People were in one costume or another – there was royalty and deposed royalty from all over including Russia and Ethiopia from which came a woman in African garb. There was a man calling himself Napoleon Bonaparte V in an old fashioned military uniform with medals. People asked me where’s that charming Japanese man? Wrong costume. Kobun and Vanja made nothing of it. Later I visited them at Vanja’s retreat Felsentor in the Alps. Vanja drove the three of us to Oktoberfest in Munich where we hung out for a few hours in the Wine Tent in his brother’s area. We didn’t drink that much but Kobun danced on a table with a barmaid. We rode the rollercoaster with five loops.

On that trip I talked to Kobun about getting down his memories of Shunryu Suzuki and those times and he laughed at me and said I wasn’t going to get anything from him to put on the Internet. Later he called me up and nostalgically waxed on about what a wonderful time it was in those early days at Tassajara and how it and all that had happened since were "thanks to Suzuki Roshi."

In a traditional Japanese home near Santa Cruz in 2001, Katrin and Kobun together wrote the kanji for the word "shine" that was used as the frontispiece for a book of vignettes about Shunryu Suzuki. They were always pretty broke and didn’t go out much. Katrin said his favorite restaurant was in Half Moon Bay. The last time I saw Kobun I treated them to dinner there – a stylish Japanese place - with their little kids and my younger son Clay.

Kobun was an artist monk with a poetic soul. He was everyone’s friend. He didn’t like to be tied down. He was there and then not there for people. Rick Fields told the story of a young man knocking on Kobun’s door and desperately begging for help, for teaching. Kobun let him in and said first let me use the toilet. After waiting for a while the visitor knocked on the bathroom door then entered to find an empty room with an open window.

There are many mentions of Kobun on cuke dot com, a website I run. Here’s Stan White, an old Shunryu Suzuki student who moved to Taos and whom Kobun ordained: "Kobun is a mystic He's an existential teacher. He does not know what he's doing, but what he does makes people practice Zen. He has students who would crawl from Albuquerque to see him for five minutes. He comes here and he disappears into the woods and we never see him - but we practice. People involved with Kobun practice."

In November of 2009 my mate Katrinka and I offered incense with Vanja at the memorial shrine for Kobun at Felsentor. Kobun’s death with his daughter was a true tragedy. Everyone was so sad. Everyone loved him. Once again he has left us with an empty room, an open window - and warm memories of Kobun.

**********************

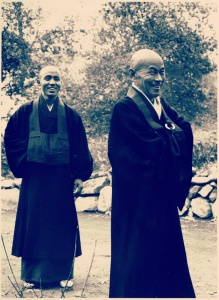

Kobun Chino and Shunryu Suzuki at Tassajara, c. 1967.