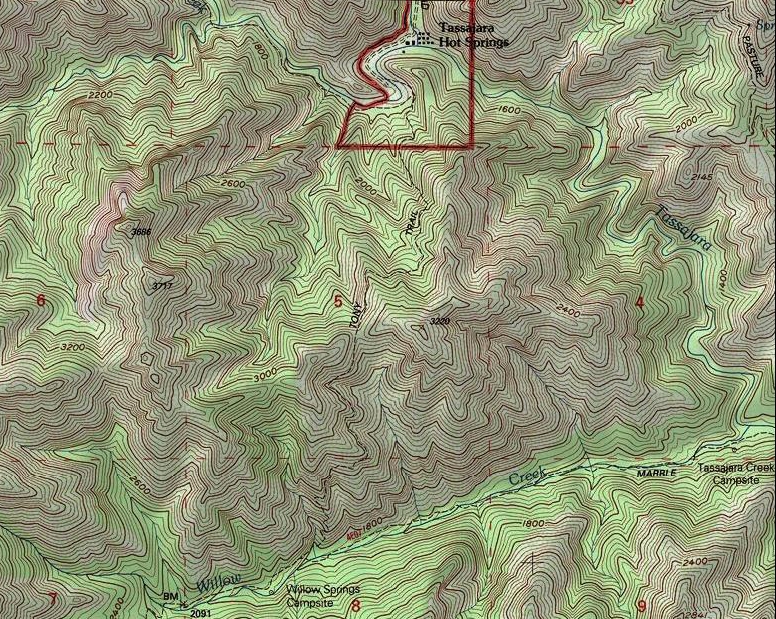

Figure 1.

The route of Tony’s Trail.

Although the path over the steep and sharply crested ridge to the south-southwest of Tassajara Hot Springs has been known as Tony’s (or Tony) Trail since at least 1899, for some reason the name Hot Springs Trail was applied to it on the United States Geological Survey’s Tassajara Hot Springs 7.5 minute quadrangle map, which was published in 1956. This resulted in the following text for the trail in Donald Clark’s Monterey County Place Names (1991):

Tony Trail. Shown on the USGS Tassajara Hot Springs quadrangle as Hot Springs Trail, this LPNF [Los Padres National Forest] trail is known today as Tony Trail. It runs from Tassajara Hot Springs (hence, the former name) to Marble Peak Trail just E of Willow Springs Camp. It was mentioned in a local newspaper as “Tony’s Trail” in 1916 and in Ruth Comfort Mitchell’s novel, Corduroy, 1923. Origin undetermined.

Tony’s Trail was named for its builder, Anthony (Tony) Dourond,1 and, as it will be seen, it appears that Mr. Dourond built this trail (or at least most of it) during the rainy season of 1898-1899. At that time Tony was serving as the resident caretaker of Tassajara Hot Springs, and his close association with the resort had already spanned a decade.

ANTHONY DOUROND (1855-1941)

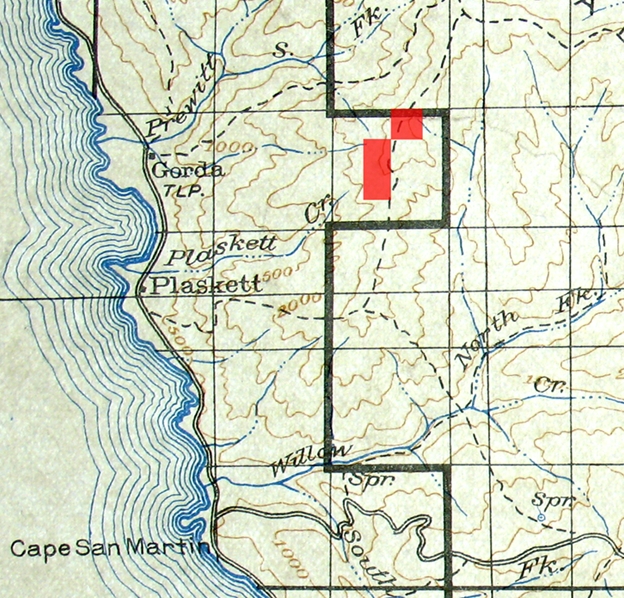

Anthony Dourond, the son a Polynesian mother and a French father, was born in Honolulu, Hawaii, on January 1, 1855.2 Nothing is known about the first 30 years of Tony’s life, but by the age of 31 he had become a resident of the Santa Lucia Mountains of Monterey County, for in August of 1886 he purchased a patent to 120 acres of California State (“State School”) land on the coastal slope of the South Coast Ridge above Pacific Valley.3

Figure 2.

The location of Tony’s Coast Ridge land.

Unless Tony held a preemptive claim to this property for an extended period of time before he purchased it, this part of his life was relatively short, for by at least early January of 1888 Mr. Dourond had become the “Surveyor and superintendent of construction” of Tassajara Road. At that time the road project probably extended to a point near or not far beyond China Camp.

TONY’S BOULEVARD

Although the Monterey County Board of Supervisors had declared the trail to “Tesahara Springs” to be a “public highway” in June of 1870,4 work on a one-lane wagon road over Chew’s and Black Butte ridges did not commence until the spring of 1886. In March of the previous year the Tassajara Hot Springs property had been purchased by Charles W. Quilty of San Jose,5 who was the first owner to have the financial means needed to build a road to the property. Within two months after Mr. Quilty bought the property survey work on the road had commenced,6 and by that time Quilty had probably entered into his business relationship with John McPhail, who was known as the “working partner.” McPhail oversaw the construction of the road while his wife, Barbara, and their children, ran the resort.7 In early May of 1886 it was reported that:

Here [near Jamesburg] I found 17 men at work building a wagon road to Tassajara Springs. It is understood that the force will soon be increased to 100 men so as to have the road ready for the traveling public by the first of July. White men are employed and receive one dollar per day and board.8

Mr. Quilty and/or Mr. McPhail greatly underestimated the task, for much of the road had to be blasted through high grade (hard) metamorphic rock that was intruded with veins and dikes of harder granitic rock. Mr. Quilty's finances became strained as the project drew on, and the road crew became tired of waiting for their pay.9 In September of 1887, nearly a year and half after construction of the road had commenced, McPhail severed his business relationship with Quilty.10

Shortly thereafter, and probably at the most by early January of 1888, Tony Dourond had taken charge of the road project, for the base camp of his road crew had become known as China Camp by that time.11 Tony’s work force consisted of Chinese laborers from San Jose, who worked for much less compensation than their predecessors, along with providing their own board.12

On January 5th, 1888, it was reported in the Salinas Weekly Index that the road to Tassajara had been built to “Within three miles of the springs” (an estimate that was probably based on linear miles), and six months later (on 6/30/1888) a note in the “Personals” column of the Monterey Democrat stated that “A splendid wagon road is finished to a point about two miles from the Springs,” and that it was expected that the remainder would be completed “within the next 30 days." On August 23rd, 1888, it was reported in the Salinas Weekly Index that “The road has been constructed to within a mile of the springs and will be finished all the way within a month,”13 and on September 13th it was reported in the “Personal and Social” column of the Index that “The editor [and owner] of the Index [William J. Hill] took his departure for Tassajara last Saturday [September 8th], to be absent two weeks.” After his return to Salinas Mr. Hill published a long article about his trip to and stay at Tassajara, which included the following statements:

The wagon road runs along the divide at the head of Miller Canyon, thence over the ridge beyond [Black Butte Ridge] and down the left [east] side of the canyon leading to the springs. It is a good mountain road, considering the roughness of the country over which it has been built. In many places the roadway had to be blasted out of the solid rock and for long distances the lower side of the grade is supported by a perpendicular wall of loose stone constructed for that purpose. Anthony Dourond was the Surveyor and Superintendent of Construction, and the road cost the proprietor, Mr. Quilty, the sum of $15,000. Mr. Lewis [the Jamesburg mail carrier] landed us at the Springs about noon [on September 9th, 1888] and we were the first passengers who went all the way thither in a wagon. Just before reaching the Springs we were signaled to halt, when a half dozen blasts were fired as a salute of welcome and to proclaim the completion of the road…

Mr. Quilty resides in San Jose and pays only occasional visits to the springs. His superintendent of work and general charge d’affairs is Anthony Dourond, who is evidently the right man in the right place, being wide awake, courteous and accommodating. He is an accomplished hunter and fisherman and, in season, keeps the camp supplied with venison and trout. It is no uncommon thing for him to go out and kill one or two deer before breakfast, and he brings in many a basketful of trout.14

Mr. Hill also noted that the resident population of Tassajara at that time consisted of “‘Tonie,’ the boss, Jim Allison the stone cutter, a woodchopper and an Italian cook.” For many decades after the completion of Tassajara Road the section from the Black Butte Ridge summit to the hot springs was commonly known to aficionados of Tassajara as “Tony’s Boulevard.”

Figure 3.

A “cut” that served as the cover illustration of the pamphlet edition of Edward Sanford Harrison’s

“Monterey County Illustrated: Resources, History, Biography,” which was published during

Tony’s Dourond’s proprietorship of Tassajara Hot Springs

David now says that citation is wrong. See

his cuke page for

explanation and elaboration.

After the road was completed Tony stayed on at Tassajara as the manager of the resort for three years (from 1888 to 1891). The following statements were selected from some of the numerous newspaper reports that mentioned Mr. Dourond during his proprietorship of Tassajara Hot Springs:

A. Dourond is in from Tassajara Springs this week, purchasing supplies for his hotel. The road to the Springs is now in good shape for travel. New baths have been constructed, and the bathing arrangements are much more convenient than heretofore.15

Tony Dourond, who is now the proprietor of the place that Ponce de Leon lost his life in hunting, was in town Saturday. He knows he has the fountain of perpetual youth, warranted to restore youth and beauty, and has been wrestling with the problem of how to get those in search of these desirable commodities to his place. He thinks he has now perfected arrangements by which people with attenuated bank accounts may enjoy the rejuvenating influences of Tassajara Springs.16

Antone Dourond is in town from Tassajara this week. He has had constructed another plunge bath for ladies, and has made other improvements at the springs for the accommodation of guests this season.17

Fishing and hunting were never better there than this season, and Landlord Tony Dourond’s attentions make every one feel like prolonging his stay as long as possible. The roads are said to be in splendid condition and the trip can be made in one day with a double team to buggy or spring wagon.18

Tony Dourond, the genial proprietor of the Tassajara Springs Hotel, came in Tuesday. He reports the present season as the most successful in point of patronage ever enjoyed by the Springs management.19

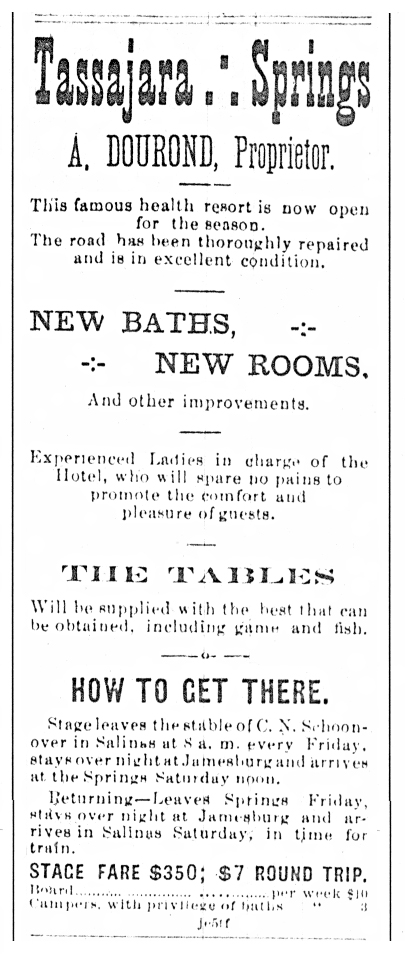

Figure 4.

An ad that ran in the Salinas Weekly Index during the summer guest season of 1890.

At some point Tony decided to once again try his hand as a mountain rancher, for on June 22nd of 1891 (and thus in his final year as manager of Tassajara Hot Springs) he purchased a patent to 162 acres of federal land in the northern Gabilan (a.k.a. Gavilan) Mountains in San Benito County, in section 14 of Township 14 South Range 5 East.20

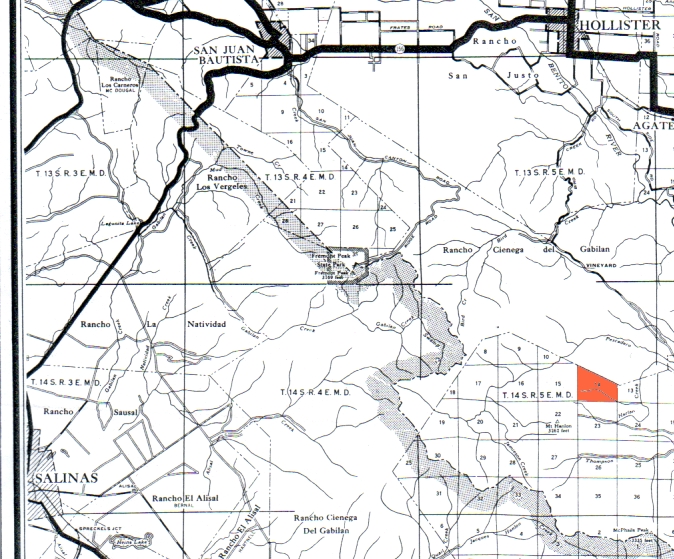

Figure 5.

Section 14 of T. 14 S. R. 5 E. (in red), in relationship to Hollister, San Juan and Salinas.

It appears that Mr. Dourond had given up on this property at some date prior to late 1897, for on October 16th of that year it was reported in a Jamesburg news column that he had gone to San Jose after spending several months at Tassajara, and five months later (on March 26th of 1898) another report from Jamesburg stated that he had come down from San Jose and went to Tassajara in the previous week. Tony remained at Tassajara until at least June 11th of 1898,21 and late in the following August it was reported that “Tony Dourond came up from Salinas Wednesday and is stopping here [at Jamesburg] for a few days’ hunting.” On the following September 27th a report from Jamesburg stated that Tony had rented a portion of the Bruce ranch (on Bruce Flats, where Tassajara Road enters the national forest), and twenty five days later it was reported in another Jamesburg news column (datelined on Oct. 15) that “Tony Dourond goes to Tassajara today to remain during the winter.”22

TONY’S TRAIL

Although Tony probably built at least most of his trail during the rainy season of 1898-1899 (when he had lots of free time on his hands), the first mention of the trail that I noticed in the copious amount of newspaper literature about Tassajara Hot Springs dates to July 12th of 1899, when a line in a “Tassajara Notes” column in the Salinas Daily Index stated that “J. H. McDougall killed a rattler at the highest point on Tony’s Trail one day last week.” Three days later (on July 16th, 1899) the Salinas Daily Index published the following two reports about an expedition to Willow Creek via Tony’s Trail, on which Mr. Dourond served as the “Guide and general factotum.”

A TASSAJARA PICNIC

A Merry Crowd Have a Jolly Time in the Mountains

Tassajara Springs, July 14, 1899.

Dear Index: We people of Tassajara are indeed enjoying our outing immensely. So many features combine to make strong limbs, healthy stomachs, good appetites and light hearts. We are a merry party, and shall sincerely regret the arrival of the hour for our parting. The return to the prosaic duties of life are not our dread, for we all feel rested and ready to assume them with renewed vigor.

As some of the guests are about to depart for their homes it was suggested that a picnic would be an appropriate event as a farewell act; so “Tony” Dourond was chosen as guide and general factotum, and no better selection could possibly have been made. Tony has long been a resident of these mountains, and is familiar with every rock and tree, brook and trail within a radius of many miles. Fourteen of us put our lives in Tony’s hands with a beautiful faith that the day’s arrangements would be a perfect success.

The automobile has not reached Tassajara, so we all carefully shod our pedal extremities with hob-nailed boots and started at 6 o’clock on Thursday morning last over what is called “Tony’s Trail,” estimated to be three and a half miles long, but we all felt sure it had been measured with a rubber tape line. This wonderful trail leads up the mountain and down again—on the other side, however. It is for the most part blasted out of a solid rock and is necessarily very precipitous, the mountain being about 1,600 feet above the hot springs. Our party started in single file, with Mr. Lund and Frank Clark in the rear leading a heavily laden pack horse. We climbed in the cool of the morning to the summit where we halted for a short rest and to admire one of the most beautiful views one can imagine. We could see the Arroyo Seco country and away beyond down into the great Salinas Valley in the vicinity of Soledad.

The valley and adjacent canyons were filled with a light floating fog, which had very much the appearance of an ocean view. We thought nothing could be grander, and were at a loss to express the full degree of our impressions.

After starting on the down grade new landscape scenes of beauty asserted themselves, one vista being down a gorge or canyon many miles long, seemingly terminating in a range of high mountains, with dense foliage on their sides up to a uniform height, above which arose peaks and pinnacles of barrenness. Niches and nooks, rills and rocks, curves and angles, with sturdy trees and delicate ferns were in all variety until we were almost satiated with the beauties of nature. Intuitively our moods changed and the suppressed merriment burst forth that bore us through the coming arduous duties of the day. Going down the mountain was more rapid than ascending, and we were soon at the picnic grounds [probably at Willow Springs Camp].

A noisy, clear, cold stream of delicious water was hurrying on down the canyon between banks covered with bushes and vines of every kind, and many varieties of delicate ferns. The host [manager] of Tassajara, James Jeffery, had donated as his contribution to the picnic a generous supply of fresh, luscious beef, which Tony barbequed to a turn, and which with the cakes, pies and other good things gave delight to our sharpened appetites.

Well, there we all were, sans souci [French for “without a care”], laughing at the sallies of wit of the bright minds among us, now and then enjoying an expression of deeper emotion from a sage or two of the party, and, incidentally, devouring food, until someone realized that we had been seated a long time around the table-cloth and suggested it might be well to make a move.

Imagine the consternation when all found themselves like Mark Twain’s frog who had been fed with shot. But a supreme effort enabled most of the party to get on their feet once more. They then gave a helping hand to those worse off than themselves, and all were astir for a delightful afternoon. Several hours were spent singing, playing cards, games, etc., by the younger people, while the sages of the party dozed and dreamed under the canopy of heaven and the foliage of madrone trees.

Miss Gertrude Quilty and Professor Duncan Sterling had their cameras along, and took “snaps” of all the striking features of the trip.23

On the return we were waylaid near the camp ground by two young ladies, Misses Rosie Vallair and Lou Thurwachter, perched on stumps on the sides of the narrow trail, and who commanded a halt, when Miss Thurwachter in gracious accents invited the entire party on behalf of Mitt Tuttle of Watsonville to come to his “Sugar Beet Camp” and have supper [at that time camping was allowed along the narrow floodplains of Tassajara Creek upstream from the hot springs].

It was 6:30 and every one of us was again ready to eat. We lined up, the Captain gave the order to “Forward march,” and we moved down the boulevard in majestic style to Sugar Beet Camp. We were most cordially welcomed by the “only” Mitt Tuttle, who had gone to much trouble and expense to provide a delicious supper—and a sufficient quantity. Joe, the Japanese cook, deserves credit for his efforts. Professor Sterling was toast master, and made the way clear for all to return most cordial thanks to Mr. Tuttle for his liberality.

We then dispersed only to gather again to spend a few hours of the evening in song and conversation before speaking the good nights.

The picnic on Willow Creek and the magnificent supper given at Sugar Beet Camp will always be remembered with sincerest pleasure by all of the participants.

ONE OF ’EM.

TASSAJARA NOTES

Mr. and Mrs. A. J. McCollum and Mr. and Mrs. J. B. Porter drove in to Tassajara Wednesday.

The envious Lying Club of Salinas sent Brewer Porter out here to cut Mike out, but the “Goddess” was too much for him. Mike put him in the “plunge” and held him there till he looked like a boiled lobster. He then rolled up him up in four pairs of blankets and kept him hot till he sweated all the “fat” off him.

Mit Tuttle and his jolly company broke camp this morning and left for their home in Watsonville. A part of them went in the steerage.

There is a well developed specimen of the “kissing bug” at the springs, and they call it Charley McD.

Thursday morning we took a walk—

Listen now and you’ll hear me talk:

The trail we took was rather stony,

But we didn’t mind ‘cause ‘twas built by Tony.

The chaperones we selected were Edith and Gus;

We all loved them dearly, ‘cause they made no fuss.

Some of us didn’t know the way,

But we were guided all right by Gertie and May,

Who skipped along and in their glee

Frightened a rattler from under a tree.

Charley followed closely by the side

Of his loving little duck of a bride

Whose name is simply Zoe—

We all love her dearly, she hasn’t a foe.

Our eyes were kept steady on Irene,

She’s the cutest girl that ever was seen.

We never forget to take her along,

She always sings us such a sweet song.

When it comes to hill climbing Mr. and Mrs. Sterling

Can climb any old hill and still keep awhirling.

Mr. Clark came last with saddle and horse,

And in front of him came the sugar beet boss;

Mr. Lund is his name, he’s from good old sod,

And when playing a game he will win “By Got.”

We were all so glad we took Mr. Hill;

He wouldn’t rest till we ate our fill.

When it comes to barbecuing fine fresh meat,

No use in fooling—Tony can’t be beat.

When we got back from our merry tramp,

We were all invited to the Sugar Beet Camp.

We were somewhat dusty, but didn’t mind a bit,

For we knew we’d be received all right by Mit.

We were happily greeted by Lu and Rose,

Who didn’t dress up in their best clothes

For fear we’d feel quite out of place;

So all we did was to wash our face.

When it comes to John Kena, Watsonville Hoy,

He is a first class Japanese boy;

The dinner he cooked will surely carry

Us over the grade from Tassy Hairy.

Tony and I have a secret we won’t tell,

But all the same, please remember Nell.

E. A. T.

Three days later (on 7/19/1899) a “Tassajara Notes” column in Salinas Daily Index included the following paragraph:

In consideration of the fact that Mr. Dourond has been instrumental in providing for the comfort of the guests in many ways, including the famous picnic at which he had his watch torn from his pocket by the bushes and lost, the party assembled last evening and presented him with a new one, which Mr. Barlow, the accommodating stage driver, had been instructed to purchase in Salinas. The presentation was quite a formal affair, Professor Sterling reading the Tassajara articles from the Index in an impressive manner just before tendering the gift. Tony was visibly affected, and accepted the compliment in a neat speech.

Later on that summer:

Tony Dourond received a handsome present of a new Winchester rifle from the boys with whom he hunted recently. He petted the present until about midnight, when he could wait no longer, and with gun in hand and deer in mind he was heard creeping up the trail.24

Tony remained at Tassajara until late January of 1900, when it was reported in a Jamesburg news column that “A. Dourond has gone to San Jose to remain.”25

TONY’S LAST WINTER AT TASSAJARA

In early September of 1906 it was reported in a Jamesburg news column that “Tony Dourond, an old-time mountaineer, and his friend, Mr. Watson, went to Tassajara last Friday” (on August 31st), and seven weeks later (on October 11th) another report from Jamesburg stated that “Tony Dourond will be caretaker at the Springs during the winter.”26

And what a winter that was! Concurrent with Tony’s return to Tassajara a massive forest fire was raging on the Big Sur Coast. This fire burned an area ranging from about five miles south of Carmel Valley to at least the northern portion of the North Coast Ridge, and inland to at least the vicinity of the Big and Little Pines (a series of newspaper reports about this fire were featured in the Spring Equinox 2004 edition of the Double Cone Quarterly). Due to the loss of ground cover it was unfortunate that the following winter was the one of the rainiest in the recorded history of California thus far. Throughout the state innumerable rainfall records were broken during the rainy season of 1906-1907. Salinas received 24.19 inches of rain that season, and by March 26th over 32 inches had fallen in Monterey,27 and thus the rainfall at both of these localities was close to 200 percent of normal.

The first storm, which averaged around an inch of rain at lower elevations in and near the Santa Lucia Mountains, occurred in the first half of November, and was sufficient to put an end to the forest fire on the Big Sur Coast. The beginning of the second, and much stronger storm, was described at Jamesburg as follows:

JAMESBURG, Dec. 11.–The heaviest windstorm that has visited this section in many years was felt here Sunday and Monday morning [Dec. 9th & 10th]. Timber was blown down everywhere; a great many trees fell across the road and the mail carrier had to chop his way through today. However the wind brought the much-needed rain and all day a warm rain has been falling.28

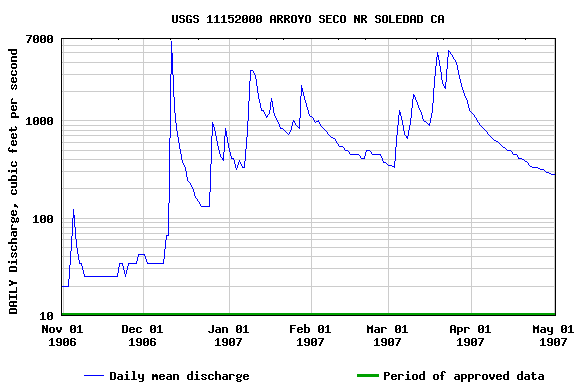

Jamesburg received about seven and half inches of rain during this storm, and if the USGS data for the Arroyo Seco is correct, this stream abruptly rose to its highest level for that rain season. As this was the first major storm, it did not result in major flooding in the Salinas Valley.

Figure 6.

A USGS data base graph of the discharge of the Arroyo Seco from November 1st of 1906 to May 1st of 1907.

Two more rain events occurred in the Santa Lucia Mountains in December of 1907, which were described in a Jamesburg news column, datelined on January 3, 1907, as follows:

We had one and half inches of rain here Christmas and an inch more last Sunday night, December 30, and one and half inches of snow Monday morning. It did not stay on long here, but there is plenty on top of the mountains yet. We have had 10 inches of rain for December.29

This brought the total rainfall at Jamesburg to about 11 inches for that season (one inch in November and 10 in December), which is probably about half of the average annual rainfall for that locality. At Salinas the rainfall was well over one half of the annual average (8.85 inches; one inch in November and 7.85 in December).30 The December rains were followed by two series of powerful storms, the first in January of 1907 and the other in the following March, and major flooding occurred in many areas of California during these events. Both floods were repeatedly described in Californian newspapers as the greatest in the state since the winter of 1889-1890.

Included in columns of the Monday, January 7, 1907 edition of the Salinas Daily Index was the following report:

THE STORM CONTINUES

Deep Snow on Mountains and Heavy Rainfall in the Valley

After a very cold night, Sunday morning dawned bright and sunny, but about 9:30 a. m. the sky became overcast with storm clouds and shortly afterwards the rain was coming down in sheets. A cold, biting wind came down upon the valley from the snow-capped mountains, the day being one of the most uncomfortable known here for many years.

This morning the mountains on both sides of the valley were garbed in white, the snowfall being unusually deep and extending far down in the foothills. It is still snowing in the mountains, and has been raining steadily in the valley all day up to the time the Index forms closed at 3 o’clock p. m.¼ The Salinas River and its tributaries are booming, and the river is expected to be bank full by tomorrow…

On the same day the Santa Cruz Surf published the following report:

THE WHITE MOUNTAINS OF CALIFORNIA

Rarely is their extent and area equal to what it is today. From Shasta to San Diego, from the Sierras to the lowest spurs of the Coast Range, practically every acre of California above a thousand feet of elevation is lying under snow. Occasional rifts in the clouds reveal the snow-capped ranges, and the tingle of the snowy atmosphere gives a glow to every cheek.

It was only along the coast and coastal valleys that the snow level remained above about 1,000 feet, for in the Central Valley, the Santa Rosa area, the Napa and Sonoma valleys, and in the Santa Clara Valley south of San Jose, snow fell on the valley floors. Needless to say, this was a major news event in California, and thus the main stories of newspapers throughout the state were dominated by both local and state-wide reports regarding this highly unusual phenomenon. Over the next two weeks a series of cold and heavily moisture-laden storms resulted in what was repeatedly described in newspapers as the most severe flooding in California since the winter of 1889-1890.

The first storm was most intense in southern California, where tremendous amounts of snow fell at higher elevations while the foothills and valleys were being drenched by heavy rain. At least four people were drowned in what the Los Angeles Times described as a “Mad rush of water” that caused the rivers and streams throughout that region to run at or above flood levels. The western Transverse Ranges and adjacent valleys were particularly hard hit. The floodwaters of the Santa Clara River were reported to be two miles wide near its mouth, and the San Fernando Valley was described as “An inland sea.” At Santa Barbara nearly all of the smaller boats were destroyed when the extremely high surf and strong winds caused them to drag their anchors and become beached, where the waves pounded them into pieces.31

Most of the newspaper coverage concerning this flood was related to the interruptions in train traffic, for prior to the widespread use of cars, trucks and aircraft, virtually all long distance transportation of passengers, mail and freight was by train. Landslides, the washing away of bridges, the collapse of tunnels, etc., brought train traffic in Southern California to a halt.

Monterey County was within the northern reaches of this event, and at about noon on January 10th of 1907 “A tremendous rush of water from the Arroyo Seco and upper Salinas” caused the Salinas River to rise to the 20 foot level at the Hilltown Bridge (this bridge was located a short distance downstream from the present bridge on highway 68). The river “Flooded thousands of acres on Moro Cojo and adjacent ranches, making huge lagoons of the beet and potato fields, and drowning cattle;” extensive flooding was also reported in the Speckles, Buena Vista and Blanco areas. It was also reported that “Vast quantities of debris are going down the river, including lots of planking and timbers, evidently from culverts and small bridges washed out by the mountain streams.” For a time the Monterey Peninsula was cut off from railroad traffic due to damages to the approaches to the Moro Cojo Bridge at Neponset.32

The sudden rise of the Salinas River caught many people by surprise, for according to a number of (often conflicting) reports, a minimum of ten people at various points became stranded, and had to take refuge on roofs or in the branches of trees. With great difficulty all were rescued.33 Although the San Francisco Chronicle reported that one of these individuals later died of exposure, when the Monterey County coroner performed his inquest he “Found the corpse very much alive.”34

The effects of these storms in and around Jamesburg were chronicled as follows:

JAMESBURG, Jan. 8—We are having one of the heaviest rains we have had for 15 years. It began Friday afternoon [Jan. 4] and still continues. Sunday [Jan. 6] it snowed all afternoon and last night [Monday, Jan. 7] it began to rain at 6 p.m., and it rained heavy all night, amounting to 2.75 inches. The roads are badly washed out and the Cachagua Creek was so high the mail carrier could not cross with his wagon. He was met by John Chew, who took the mail across on horse back. He reports the road from Laureles Ranch up in very bad condition, being washed out so he had to take down fences and go through fields to get here. We have had 6¼ inches of rain for this storm, and its still rainy, and 16¼ inches for the season.35

JAMESBURG, January 14.—Its rain, rain, then snow and then some more rain: it both snows and rains every day, and while here the snow has not more than covered the ground and does not lay long, on the higher altitudes it is accumulating and is now about five feet on the summit [of Chew’s Ridge]. There has been over twenty inches of rain for the season so far and it’s still raining. The roads in every direction are badly washed, and bridges and culverts are gone. The Laureles Grade is reported impassable.

Last Friday [Jan. 11] Mr. Webster, the mail carrier, could not reach the post office, and was compelled to stop at Mrs. Lewis’ place, where John Chew met him and brought the mail over on a saddle horse, the high water in the Cachagua Creek and a washout on the road being the cause.36

As evidenced by the following report from Jamesburg the stormy weather in the northern Santa Lucia Mountains continued until January 18th:

JAMESBURG, January 21.—At last the storm has broken and three days of lovely sunshine have been given us. This morning a regular “Chinook” wind was blowing which ought to eat into the snow.

The snowfall on the highest mountains is probably the heaviest ever known. It is impossible to get to the summit, but from the rain which has fallen here, over thirteen inches, there must be at least nine feet of snow on a level where none has melted, and much deeper in drifts. There is three and a half feet of snow at Frank Bruce’s place half way up the mountain [i.e., Bruce Flats, where Tassajara Road enters the forest], and he has been compelled to bring his hogs down to the lower lands. One and half feet of snow fell there last Wednesday night [Jan. 16]. The rainfall here Wednesday night was three inches, making a total of thirteen inches for January and twenty-four for the season. Rain continued to fall on Thursday.

The barns of Frank Bruce and G. I. Hallock were crushed down by the snow, as was also an old barn belonging to W. Cahoon.37

A subsequent report from Jamesburg, datelined on January 28th, stated that “The warm weather has been melting the snow quite rapidly, except at the summit, where it is still very deep,”38 and another report from Jamesburg, datelined on February 14th, stated that:

T. Call of Tularcitos went to Tassajara Springs Sunday, and reports that there is one and half feet of snow on Chew’s Ridge yet, and found Tony Dourond well and hearty, and glad to see him.39

By mid-March of 1907 annual rainfall records at innumerable localities in California had been broken, so when another series of powerful storms hit the state in the latter half of that month the stage was set for another period of major flooding. In contrast to the January event, the March rains were warmer and more heavily impacted the northern part of the state, but like the floods of January, the March event was repeatedly described in newspapers as the worst in the state since the winter of 1889-1890. The Central Valley was particularly hard hit this time, especially in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta region, where exceptionally high water and the crumbling of levees caused extensive flooding. Stockton was flooded twice, and at Sacramento, where the levees held, the view from the dome of the State capitol was described as “one brown sea of flood waters as far as a spyglass can see.” 40 San Mateo, Santa Clara, Santa Cruz, San Benito and northern Monterey Counties were also heavily impacted (as the heavy rains occurred only in the northern half or so of Monterey County, the Salinas River did not reach the level that it had in the previous January).

In Monterey County the peak flooding occurred between Friday, March 22nd, and Sunday, March 24th. On Friday night a rainstorm commenced, which was described by a number of reports as being the heaviest in 20 years, and it was said to have ended with massive crescendo on Saturday. On that day the Arroyo Seco reached 16.30 feet at the gauging station near the Greenfield bridge, a level that was higher than that of the previous January, and it was also on Saturday that the peak flooding along the Big Sur coast occurred, as evidenced by the following report that was published in the March 26, 1907 edition of the Monterey Daily Cypress:

BIG FLOOD AT SUR

Houses Are Washed Away and Others Wrecked—Roads Almost Impassable

SUR, March 24—A terrific storm has raged in the coast section for a week. All the streams are running over their banks, bridges are gone and roads are impassible.

News was received this morning that Mill [Bixby] Creek rose twenty feet yesterday afternoon [i.e., on Saturday, March 23rd], washing out all the bridges.

The flood carried off the lime kiln barns, smashing them into the house occupied by the family of J. C. Silva and Thomas Fussel, totally wrecking the house. All of Mrs. J. C. Silva’s furniture is ruined.

The house of Al Cushing was saved by a log turning the flood, but all of his outhouses were swept down stream.

The Sur post office was washed up against the hillside.

Two feet of water now stands in H. M. Hoge’s parlor.

Piles of driftwood are now wedged up against the Palo Colorado schoolhouse.

The stream has now gone down some, and unless the rain continues, most of the damage is over.

Last Sunday night it began raining and has continued to do so up to this time. The coast mail could not reach the Post post office last Monday because of the swollen rivers, and could not get back to the Sur post office until Wednesday, where it has been until today, when the stage driver will try to get to Monterey by horseback [at that time the Post Post Office was located in what is now Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park, and the Sur Post Office was located near the mouth of Bixby Creek].41

There are no roads whatever, hardly a trail left, and in some places not even that. Most of the bridges are washed out and all of them are more or less damaged.

At Mal Paso, where the road was built up with rocks, the road slid out and at Double Gulch one bridge is gone and the place is all slides.

At Garrapatas the bridge still stands but the water has cut deep channels on each side so the creek has to be forded to cross at all.

It is reported that a large mass of rock and earth slid out of the Point Sur Light House Rock, and all the women have moved up to the Swiss Canyon Dairy to stay until the storm is over.

The lime kilns can be reached only by foot. All the bridges are gone.

Between the Hotel Idlewild [on the Little Sur River] and Mrs. Cooper-Vasquez’ [on Rancho El Sur] for a distance of about one hundred feet the road has slid into the canyon.

R. M. Smith with a gang of men is out working on the roads, but it will be weeks before they will be fit for travel.

Such a storm as this has never been witnessed by anyone in the coast section before.

The preceding report was also published in the March 30th edition of the Salinas Weekly Journal, under the title “Terrific Storm in Coast Section.” Another report about the flood on the Big Sur coast was published in the March 27th edition of the San Jose Herald:

STORM’S DAMAGE

Pacific Grove, March 26.—Reports have been received in Monterey of unexampled havoc by the long protracted storm all along the coast to the Sur Lighthouse. The roads have become chaotic bogs or have slid sheer away into the yawning gullies below. Bridges have been carried out to sea and houses and barns have been wrecked. Mill Creek rose 20 feet. The lime kiln barns were demolished and wreckage crashed into a house occupied by Thomas Fussels and J. C. Silva. The Sur postoffice was carried away by the flood.

Due to the loss of the Salinas Index during this period (from 2/1 to 5/27 of 1907), the only information that has survived about storm-related conditions in the Jamesburg area comes from the following report that was published in the Salinas Weekly Journal:

JAMESBURG, March 31.—We are having all kinds of weather. It has rained so much that the ground is thoroughly soaked and the creeks are very high. We have had more than our share of rain this winter. The roads are washed out very badly. All bridges between here and Laureles [now the site of Carmel Valley Village] are washed out. We have had 36 inches of rain for the season. On Tuesday and Wednesday mornings [March 26 & 27] the ground was covered with snow.42

The average annual rainfall at Jamesburg is probably less than twenty four inches, for at the University of California’s Hastings Natural History Reservation, about two miles east-northeast of Jamesburg, the average annual rainfall is 20.87 inches.43

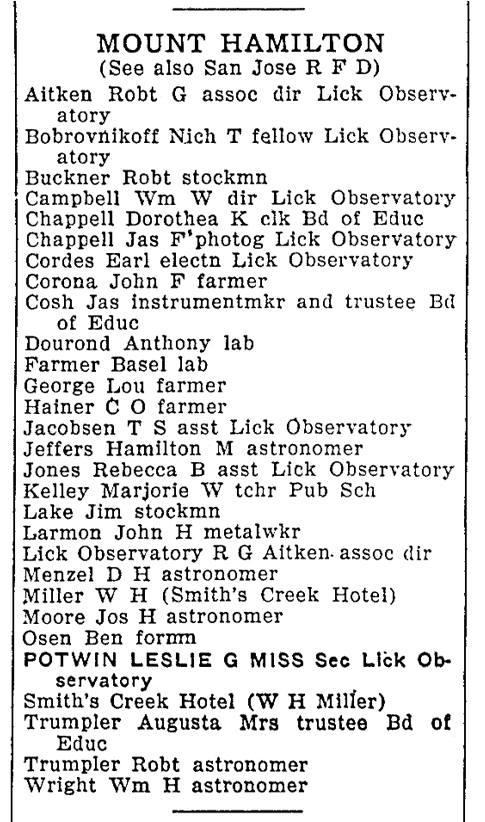

Figure 7.

The residents of the Mount Hamilton precinct as listed in the 1929 edition of Polk’s San Jose and Santa Clara County Directory.

THE REMAINDER OF TONY’S LIFE

By 1909 Mr. Dourond had moved to a rural area of the Sierra Nevada in Tuolumne County, where, according to the census of 1910, he was employed at an electric power plant, and by 1918 he had returned to Santa Clara County, for by the first of January of 1919 he was living in the vicinity of the Lick Observatory on Mount Hamilton. Although the census of 1920 listed Mr. Dourond as livestock farmer, directories for San Jose and Santa Clara County from 1919 to 1934 listed his occupation as a laborer. This is supported by information provided in the census of 1930, for it lists Tony’s occupation as a laborer who was engaged in county work. As county work in that part of Santa Clara County was probably limited to the maintenance of Mount Hamilton Road, I suspect that this was Tony’s occupation.

Tony was not listed in the Santa Clara County directories published after 1934, but it appears that he remained a resident of that county, for according to his California State death record, he died in Santa Clara County, at the age of 86, on December 8, 1941. I reviewed all of the editions of the San Jose Mercury published in the first few weeks after Tony’s death, but failed to find an obituary, or even a death notice.

1 The name Dourond is extremely rare, so much so that all of my searches of online and offline data bases (such as the soundexes of censuses) yielded only one person, whose first name was Anthony, and who was born in Hawaii in the mid 1850s. Even a very recent Google search for Dourond yielded only one result, and this was a link to a Double Cone Quarterly article that I had written about Tassajara Road several years ago. It is thus fairly certain that the other Californian records listed under the name Anthony Dourond that do not include biographical information (such as land patents) also refer to this individual.

2 U. S. censuses of 1910, 1920 and 1930; California death records online database.

3 Monterey County State Patent Book 1: 214. In March of 1853 the Congress of the United States granted to the State of California the 16th and 36th sections of each township in the state “for the purposes of public schools” (U. S. Statutes at Large 10: 244-248), and the California State Land Commission was authorized to sell these properties if it was deemed to be in the best interest of the state. Tony’s land consisted of the northeast quarter of the southwest quarter, the southeast quarter of the northwest quarter, and the northwest quarter of the northeast quarter of section 16, township 23 south range 5 east, M. D. M. The patent was granted on Aug. 12, 1886.

4 Minutes of the Monterey County Board of Supervisors, Book B: 65. June 17, 1870.

5 Monterey County Deed Book 10: 94-95. Eight months later it was officially recorded that the Tassajara property had been purchased with the money of Mr. Quilty’s wife, and was thus part of her personal and separate estate (Monterey County Deed Book 10: 280). Mary Hagan Quilty had inherited a substantial estate from her father, James Hagan, who was the founder of a number of the early utility companies in California.

6 “Health Resorts.” Salinas Weekly Index, May 21, 1885.

7 Card, Carol. “A Spa is Born.” What’s Doing 3 (12), June, 1949.

8 “Random Notes, Picked Up in the Corral de Tierra and Carmel Regions.” Salinas Weekly Index, May 6, 1886.

9 Card, Carol. “A Spa is Born.” What’s Doing 3 (12), June, 1949.

10 An entry in the “Personal and Social” column in the September 9, 1887 edition of the Salinas Weekly Index states that “Mr. Quilty has purchased Mr. McPhail’s interest in Tassajara Springs and is now sole owner of that property.” Four months later a “quit claim” deed, from John and Barbara McPhail to Mary Quilty (dated Jan. 9, 1888), was recorded (Monterey County Deed Book 17: 112-113).

11 “Altitudes in Monterey County,” Salinas Weekly Index, January 5, 1888.

12 Card, Carol, “A Spa is Born,” What’s Doing 3 (12), June, 1949; McDonald, Marilyn, “The History of Tassajara Hot Springs,” unpublished typescript, 1985.

13 “Tassajara Springs,” Salinas Weekly Index, 1/5/1888; “Tassajara Springs” and “Personals,” Monterey Democrat, 6/30/1888; “Tassajara Springs,” Salinas Weekly Index, 8/23/1888.

14 Hill, William J. “Tassajara Springs.” Salinas Weekly Index, 10/4/1888. A transcription of Mr. Hill’s entire report was published in the Winter Solstice 2000 edition of the Double Cone Quarterly.

15 “Brevities,” Salinas Weekly Index, 6/5/1890.

16 “Personal and Social,” Salinas Weekly Index, 8/14/1890.

17 “Personal and Social,” Salinas Weekly Index, 5/14/1891.

18 “Tassajara Springs,” Salinas Democrat, 6/6/1891.

19 An item in one of the uncaptioned local news columns in the Salinas Democrat, 7/4/1891.

10 Bureau of Land Management’s General Lands Office records website. Tony’s land consisted of lot 10 of the northwest quarter of the southwest quarter, lot 11 of the southwest quarter of the southwest quarter, lot 12 of the southeast quarter of the southwest quarter, and lot 13 of the southwest quarter of the southeast quarter.

21 Willow Tree, “Notes from Jamesburg,” Salinas Weekly Journal, 10/23/1897; Pinafore, “Jamesburg Gleanings,” Salinas Weekly Index, 3/31/1898; “Hop at Tassajara,” Salinas Weekly Journal, 6/4/1898; “Party at Tassajara,” Salinas Daily Index, 5/15/1898.

22 Willow Tree, “Notes from Jamesburg,” Salinas Weekly Journal, 9/3/1898; Pinafore, “Jamesburg Gleanings,” Salinas Weekly Index, 9/22/1898; Willow Tree, “Jottings from Jamesburg,” Salinas Weekly Journal, 10/22/1898.

23 Marilyn McDonald’s The History of Tassajara Hot Springs features a photograph titled “Hiking on the Tony Trail, c. 1900.” As Marilyn’s informants (many of which provided to her their photographs) included descendants of Gertrude Quilty’s sister’s family (May Quilty Jeffery, who was also one of the participants of this outing), it is possible that this is one of Gertrude Quilty’s “snaps.” The Quilty sisters were two of the eight daughters of Charles Quilty, the owner of Tassajara at that time.

24 “Tassajara News,” Salinas Daily Index, 8/22/1899.

25 Pinafore. “Jamesburg Gleanings,” Salinas Daily Index, 1/31/1900.

26 Willow Tree, “Notes from Jamesburg,” Salinas Weekly Journal, 9/8/1906; Pinafore, “Jamesburg Gleanings,” Salinas Daily Index, 10/12/1906.

27 “Rainfall in Salinas from 1872 to 1923,” Salinas Daily Index, 6/9/1923; “Storm in Monterey,” Monterey Daily Cypress, 3/26/1907.

28 Pinafore. “Jamesburg Gleanings,” Salinas Weekly Index, 12/20/1906.

29 Willow Tree. “Notes from Jamesburg,” Salinas Weekly Journal, 1/12/1907.

30 “Rainfall in Salinas from 1872 to 1923,” Salinas Daily Index, 6/9/1923.

31 Los Angeles Times: “Mad Rush of Water,” 1/10/1907; “Ventura County Drenched,” 1/9/1907; “Fernando Valley an Inland Sea,” 1/10/1907; “Great Damage at Santa Barbara,” 1/10/1907; etc. etc. etc.

32 “The Storm Continues,” Salinas Daily Index, 1/10/1907; “Salinas River Booming,” Salinas Weekly Journal, 1/12/1907; “Fatal Floods in Salinas Valley,” San Francisco Chronicle, 1/12/1907.

33 Ibid.

34 “Fatal Floods in Salinas Valley,” San Francisco Chronicle, 1/12/1907; “Had Hard Time of It,” Salinas Daily Index, 1/11/1907.

35 Willow Tree. “Notes from Jamesburg,” Salinas Weekly Journal, 1/19/1907.

36 Pinafore. “Jamesburg Gleanings,” Salinas Daily Index, 1/16/1907.

37 Pinafore. “Jamesburg Gleanings,” Salinas Daily Index, 1/23/1907.

38 Pinafore. “Jamesburg Gleanings,” Salinas Daily Index, 1/30/1907.

39 Willow Tree. “Notes from Jamesburg,” Salinas Weekly Journal, 2/23/1907.

40 “Flood Over State,” Monterey Daily Cypress, 3/26/1907.

41 Clark, Donald. Monterey County Place Names. Kestrel Press, Carmel Valley, 1991.

42 Willow Tree. “Notes from Jamesburg,” Salinas Weekly Journal, 4/6/1907.

43 This figure is based on a graph of monthly rainfall averages from 1939 to 1999 that is posted on the Hastings Reservation’s web site.