Les Kaye (and Mary too) Kannondo - the Los Altos, CA, Zen group Les where Les is abbot

Interviews with Les Kaye

Interviews with Les Kaye

Les Kaye's Zen life - submitted to DC to read for his podcast 🔊 - 2020

The Tenfold Prohibitory Precepts - by Kobun Chino and Les Kaye

Interview with Les Kaye on Zen in Business dot com

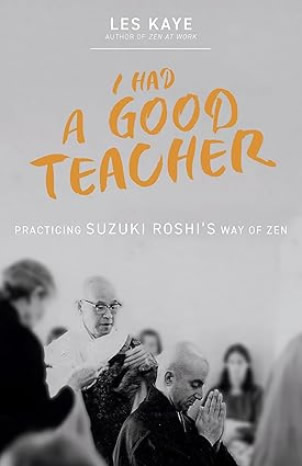

I Had a Good Teacher

I Had a Good Teacher

“interweaves Les Kaye’s Dharma talks with personal stories to reveal the subtleties of integrating Zen practice into a life of work and family. It includes fascinating memories of Suzuki Roshi and short writings about events at the zendo, including the time Steve Jobs visited Les for guidance integrating work and spiritual practice. I Had a Good Teacher is an excellent introduction to Zen in daily life, a warm portrait of a great Zen teacher, and a reminder to meditators to return to basics, keep their meditation real, and practice awareness all day long.” - on Amazon

Brief interview with Les by DC plus comments in Interviews in which there is a Brief Memory of Shunryu Suzuki

Sweeping Zen interview with Les - Whole thing below

Les Kaye asks a question - in Comments

Brief interview with Les by DC from which a Brief Memory

and from which a Brief Memory of Mary Kaye's on Suzuki the thief

Les and Mary Kaye are mentioned 17 times in the Haiku Chronicles Part I

9-05-14 - Remembering Suzuki Roshi - A talk given by Rev. Edward Brown, Rev. Peter Schneider, and Rev. Les Kaye in honor of the 50th anniversary of Suzuki Roshi's arrival in America, on Saturday, May 23, 2009, at City Center. (from the SFZC site) - NOT THERE

The Spiritual Vision of Steve Jobs - by Les Kaye

Books by Les Kaye

NEW 2018: A Sense of Something Greater: Zen and the Search for Balance in Silicon Valley (see below)

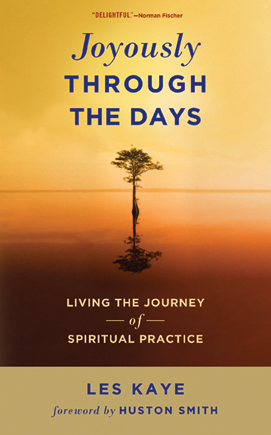

Joyously

Through the Days: Living the Journey of Spiritual Practice

with a forward by Huston Smith -

Wisdom Publications link [Amazon Link]

Joyously

Through the Days: Living the Journey of Spiritual Practice

with a forward by Huston Smith -

Wisdom Publications link [Amazon Link]

Kaye, Les, Zen at Work: a Zen

Teacher's 30-Year Journey in Corporate America. Crown, 1996.

Kaye, Les, Zen at Work: a Zen

Teacher's 30-Year Journey in Corporate America. Crown, 1996.

[Les has been a priest at the Los Altos Zendo since Suzuki

ordained him in 1971 and for many years he combined his priest practice

there with his job at IBM.]

Amazon link

Search for "Les Kaye" on cuke.com and find much more.

There are mp3s and videos and more of Les on the Internet.

DC talks to LES KAY - talked on phone in 93 and saw on 10\13\94 and talked to him there in his office and to his wife, Mary, as well with him in their kitchen. - dc

DC: Les was at Tassajara for a week with his wife and children. He was asked if his car could be used to go pick up some Japanese priests because there were more people coming in than their best vehicle could carry. He recalls:

LK: I remember when all those great Zen teachers were at Tassajara, Dick Baker saying now's a great opportunity to ask some of these great teachers a question and I asked:

"What's the best way to establish Buddhism in America?" So they spoke amongst themselves and agreed that each one wanted to answer it and I remember Yasutani speaking in Japanese and being translated and I remember Edo getting up and being very dramatic and Soen too and Maezumi. I remember Suzuki Roshi getting up and saying, "I have nothing to say," and we all roared and it was over. He went out the side door.

DC note: What I had written in my notes was "and then you asked" rather than "and then I asked" which I interpreted while working on Crooked Cucumber as me David but which now it's clear meant him Les and I wrote "you" for him - I don't remember asking it or saying the above and he remembers asking it so obviously he said all of the above. As a result of this confusion I incorrectly attributed to myself this story in Crooked Cucumber. Sorry. It's corrected in the version of Crooked Cucumber on cuke and in the Errata section.

LK: When Suzuki Roshi came here [to Los Altos] to give his talks, after zazen and his talk and he'd always want to talk to my wife in the kitchen and she said oh he'd just ask how I was doing and we'd say hello and we were both into bonsai. Once, she said, we were at Tassajara and I told him I had found a new seedling to make a bonsai with and it was planted in a small dish and we went outside and I showed it to him and he said, "Thank you," and took it off to his cabin. And she said I do remember that once when we were at Tassajara he was sitting next to me at a meal in the dinning room and I was drinking a coca-cola and he just leaned over and took a big sip out of it.

DC note: All of us who came to ZC were different in one way or another - so many of us had come through LSD and being hippies or beatniks or artists - but Les came from a unique sociological niche - working for IBM. I saw him as more dependable like Japanese. He knew what he wanted and decided to do it and did it. I think Suzuki recognized this in Les and ordained him to be a priest at the Los Altos Zen Center. Suzuki had learned you can't always depend on Americans but I think he saw in Les someone who was committed and would follow through. Les has always also been pretty separate from the SFZC and the rest of the sangha as is the case with some other Suzuki disciples and which is natural. Again, he sticks to home and doing his duty.

Les told about how he developed a relationship with Yamamoto [?] at Shumucho [Soto Zen headquarters in Japan] and gave him a book on Oryoki [ceremonial zendo eating method with nested, wrapped bowls] he'd written and a year or so latter says he received in the mail a copy of it with the sketches replaced with photographs but it was word for word his book with no credit given.

Maybe that's one reason why Les refused to be interviewed further. He said if he told me something then he couldn't use it in his book. I said I didn't think that was so, but I respected his decision.

When I was working on digitalizing the Suzuki lecture and archive and making it more available through hard drives, CDs, and the Internet, I talked to Les about his group making a contribution to the SFZC fund for this and he and his board expressed suspicion of the usefulness of such a project and whether they'd really get anything for their contribution. So they declined. I said okay, that it would be shared with them anyway. When I gave a digital copy of the archive to Les, he thanked me and was friendly, but said he wasn't so sure this should be done, that we already have Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind and why do we need more than that and do we really want people putting CDs of Suzuki's lectures in the CD players of their cars and listening to it on the way to work? I said it's not a CD to play, it's a data disc with all of Suzuki's lecture transcripts, audio, and video and I didn't think about what other people were doing and that all I thought about was preserving it and making it available for free and he was free to do or not do anything he wanted with his copy and could have more copies anytime.

Les is one of three disciples of Suzuki whom Suzuki's son, Hoitsu, gave transmission to in order to complete, he felt, the work of his father who died before he could do so - and because they didn't have en or compatibility with Richard Baker. The other two are Mel Weitsman, abbot of the Berkeley ZC and Bill Kwong of Sonoma Mt. Zen Center. Les said he did the three tokubetsu sesshin in Japan (and maybe in the US) to get

Les Kaye Sweeping Zen Interview

Completed on October 29, 2010

Revised on April 14, 2011

Les Kaye started work in 1958 for IBM in San Jose, California, and over thirty years held positions in engineering, sales, management, and software development. He interested in Zen Buddhism in the mid 1960s and started Zen practice in 1966 with a small group in the garage of a private home. In 1970, he took a leave of absence to attend a three-month practice period at Tassajara Zen monastery in California and the following year was ordained as a Soto Zen monk by Zen Master Shunryu Suzuki. In 1973, he took an additional leave of absence to attend a second practice period, this time as head monk, and in 1984, Les received Dharma Transmission, authority to teach, from Hoitsu Suzuki, son and successor to Shunryu Suzuki. He was appointed teacher at Kannon Do Zen Center in Mountain View, California. He and his wife Mary have two adult children and a grandson and live in Los Altos, California.

His first book was Zen

at Work. His

next book was Joyously

Through the Days: Living the Journey of Spiritual Practice(Wisdom

Publications, 2011) is his latest.

Website: http://www.kannondo.org/

Transcript

SZ: How did you find your way to Zen practice?

LK: Sometime around 1960, I listened to a talk about Zen & Buddhism by Alan Watts on the local PBS radio station. He spoke of seeing life with a totally different world view than what I was used to, but that seemed somehow familiar. It was an exciting and strange feeling – I felt inspired to follow up. I made it a point to listen to Alan Watts on his weekly Sunday night program and read a few of his books, becoming more and more interested. I believed that to really study and practice Zen, one had to go to Japan, not an option for me.

In 1966, while reading the San Francisco Chronicle, I accidently came across an article about the San Francisco Zen Center. I had no idea such a thing existed so close to home. Some weeks later, I skipped out early from a business seminar in the city and went to SFZC. I found an old, creaky building on Bush Street, formerly a synagogue built at the turn of the 20th century. It was dark and quiet in the musty halls, except for sounds coming from an office. Entering, I saw two tall, bearded young men, operating a mimeograph machine. There was also a Japanese gentleman, wearing a hat, sitting in a chair, reading a Japanese newspaper. I wondered, “Is that the Zen master?” I told the young men that I wanted to know more about Zen but that I lived fifty miles away in San Jose. They directed me to an affiliated center in Los Altos – Haiku Zendo – about twenty miles from home. Suzuki-roshi visited there weekly to lead meditation and give a talk. So my wife and I started going to Haiku Zendo on Wednesday nights later that year.

SZ: At Haiku Zendo I imagine that you and your wife have the opportunity to practice with Kobun Chino roshi. Could you take a moment or two to relate your memories of him to us?

LK: Everybody was attracted to Kobun because he gave the sense of what it is like to be a spiritual person. He was warm hearted, gracious, generous, and playful, with a very wide world-view. At the same time, he was much like a loveable absent-minded professor, who is not too concerned with managing the affairs of everyday life but whose entire focus is on expressing his vision of truth and sharing it with others.

SZ: Tell us about your teacher, Hoitsu Suzuki roshi. I hear that his style is very different from that of his father, the great Shunryu Suzuki roshi.

LK: Hoitsu is very much like his father in many ways. He is dedicated, observant, generous, approachable, and caring. He is more outgoing, more demonstrative, than his father, who did things with less flair. Hoitsu is a fun loving individual, who enjoys socializing. However, when he puts on his robes, and when he gives a lecture, becomes very serious.

SZ: Tell us about Suzuki roshi also. I never get tired of hearing stories about the early forbearers of Zen in the United States.

LK:Here is one example of how Suzuki-roshi expressed his wisdom and compassion in everyday relationships. The event took place during my priest ordination ceremony.

Almost 50 people crowded into Haiku Zendo that Saturday afternoon in 1971. My mother, living in San Francisco, arrived fifteen minutes after the ceremony had begun. She was nervous as she entered the packed room. Her middle-aged, middle-class son, with a nice family, nice job, nice home, and promising future, was preparing to become immersed in a mysterious religious world beyond her comprehension. She was certain that I was throwing away everything required for the “good life.” She could not hide her anxiety. I can still see Suzuki-roshi’s eyes glancing at her as she entered and took a seat someone offered her near the platform. Very gently, he reached over, put his hand on her shoulder and said, “You have come just at the right time.”

From Zen at Work, p. 88.

SZ: What, to your mind, is a common pitfall one may encounter in their Zen practice? How can one know that they have encountered it and what can they do about it?

LK: I would not characterize it as a pitfall but rather a difficulty that many people encounter. The difficulty becomes the opportunity of a lifetime when it is recognized and not avoided. After starting meditation practice, many individuals encounter resistance to continue, even when they know – and have experienced – that practice is one of the best things they can do for their lives. They are not aware of the reason for the resistance; it remains unrecognized by consciousness. It has to do with the perceived “cost” of practice, what individuals feel they have to “give up” to get what they want. They go through an unconscious “cost versus value” tradeoff. Fundamentally, people come to Zen practice out of a feeling to be more in touch with their spiritual nature. But this intention gets short-circuited by the mind’s craving for comfort, excitement, entertainment, and fame. Practice does not provide such things. Instead, what people first experience is boredom, which is not what they expected. And they do not recognize that their boredom is not inherently negative – the mind is free of the cravings and so can be spiritually creative. It is an opportunity for hidden things to appear: our old habits and reactive tendencies that have been getting in our way, the inherent beauty of everything, and the wisdom that we never knew we had. So, many quit out of impatience and disappointment for not getting what they want.The best way to respond to boredom and disappointment is through determination to continue despite the feelings and to recall what brought us to practice in the first place.

SZ: I have a two-part question. First, what are we talking about when we say the word emptiness?

LK: From a practical, everyday standpoint, “emptiness” is an “empty” mind, free of the cravings as described above, a mind ready to accept anything that appears, without judgement.

SZ: Also, how is the Heart Sutra factor into this teaching on emptiness? Why is an essential realization to have on our journey?

LK: The Heart Sutra speaks of “emptiness” as the aspect of our self that is universal, without limits, that has no unique personality, that cannot be described in everyday terms, and that is constantly changing. Both views of emptiness – the practical and the universal – are vital in our lives, the first so that we can live our active, everyday lives in a selfless way, untroubledway, the second so that we realize there is something very big taking place in this world, greater than our own individual life, but that our individual life expresses. This realization is the basis for the end of suffering.

SZ: Suzuki Roshi said, “When you do something, you should burn yourself completely, like a good bonfire, leaving no trace of yourself.” This is from the classic Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, for our readers. What is your take on what he means by this?

LK: Express your true self, your Buddha nature, by putting your entire awareness and energy on what you are doing. Don’t allow the quality and completeness of your effort to be compromised by distraction and desire. It also means tidy up after your activity; don’t leave a mess for others. In other words, be mindful of others.

SZ: What are the markings of a good Zen teacher? What qualities should a student be looking for?

LK: I’ve always felt that the best starting point is found early in the Metta Sutta, where it describes the wise and peaceful Bodhisattva: Let one be strenuous, upright, and sincere, without pride, easily contented and joyous. I think this is the attitude we should be looking for in our teachers, mentors, and role models, and – as Zen students – the attitude we should be cultivating in ourselves. To be more specific, there are a number of personal attributes we should look for and use as a guide for our own practice:

- Integrity: does not waver from acting according to vision and principles

- Trustworthy: keeps promises, fulfills commitments, does not make unnecessary excuses

- Sincere: means what he/she says

- Morality: maintains highest ethical standards

- Work Ethic: undertakes necessary tasks without hesitation

- Generosity: gives of self and possessions according to needs of others

- Humor: light hearted, helps others feel at ease

- Self-awareness: recognizes and accepts own strengths and weaknesses

- Confidence: not deterred by ambiguity or uncertainty

- Selflessness: sets aside ego, ambition, and desires for the benefit of others

- Wisdom, insight: recognizes the unseen, spiritual dimension of Reality; understands that the phenomenal world is not all there is, and acts accordingly.

- Courtesy, social skills: expresses appreciation to others for acts of kindness and generosity, engages easily with others, comfortable and attentive in relationships.

SZ: You’ve written an important book, Zen at Work. I think this book is particularly useful for those who think you need to leave your job (and perhaps wife and kids) to fully engage a Zen practice. What do you hope readers get out of your book?

LK: I think your question provides its own answer. Plus, not only do we not need to drop out, we have to learn to practice in the challenging daily life of work, family, commuting, technology, politics, and greed.

SZ: Your second book was published in April of 2011. Could you tell us a bit about it?

LK: Its title is: “Joyously Through the Days: Living the Journey of Spiritual Practice.” It consists of short essays and stories that reflect my own experience of the various ways that spirituality and Zen practice can be expressed in ordinary human affairs, in our relationships and our actions. In a nutshell, this book is about selflessness. My original title was “From Suffering to Selflessness,” which indicates what my purpose was in writing the book. But the publisher thought that this title would be too dark for the reading public, and wanted something lighter, more appealing. Another possible title that I considered was “Out of the Monastery, Down from the Mountain.” I was hoping to introduce the notion that Zen practice has changed permanently by coming to America, that it is now practiced primarily by lay people with responsibilities in the everyday world, rather than by monks in the monastery.

SZ: Rev. Kaye, thank you for participating. In closing, what book(s) would you recommend to someone interested in Zen practice?

LK: Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind – Shunryu Suzuki

Buddha – Karen Armstrong

What the Buddha Taught – Rahula

Unseen Rain – Rumi

A Primer of Soto Zen– Masunaga

A new book by Les Kaye, one of Suzuki-roshi's early students, and the current abbot of Kannon Do Zen Center in Mountain View, California. The book is A Sense of Something Greater: Zen and the Search for Balance in Silicon Valley. It is about how individuals are exploring their spirituality and searching for ways to include Zen practice with their work and family responsibilities in the modern world.

Parallax Press link for this book. Amazon link.

**********************************************************

"A truly surprising, brilliant, and wonderful book. Reading it, you suddenly see that there is something greater that is before us, right here, right now. Les Kaye and co-author Teresa Bouza reveal a different kind of mind (and heart) in the midst of Silicon Valley and of our lives. This marvelous book is not only about the search for balance but for meaning in the midst."—ROSHI JOAN HALIFAX, Upaya Zen Center

“Zen meditation may call forth images of Japanese rock gardens and old monasteries, but Les Kaye places it naturally in the midst of twenty-first- century urban American life. Using interviews with individual practitioners by Teresa Bouza, A Sense of Something Greater vividly illustrates how this simple practice can offer remarkable clarity and ease to those who work in competitive, high-tech, high-stress settings.”—KAZUAKI TANAHASHI, Painting Peace at a Time of Global Crisis

“A warm, remarkably intimate introduction to a spiritual community in the heart of Silicon Valley. Through personal interviews with the community’s members, we meet the real people of the Valley, as they struggle to find their bearings in the fast lane of the high tech world; through the wise counsel of the community’s leader, Les Kaye, we are welcomed into the ancient tradition

of Soto Zen, where meditation is our most natural act and spiritual practice is its own reward.”

—CARL BIELEFELDT, Associate Professor of Religious Studies, Stanford University

As an Amazon Associate Cuke Archives earns from qualifying purchases.