[205]

Chapter Twelve

Sangha

1961-1962

If you want to study, it is necessary to have a strong,

constant, way-seeking mind.

Bill McNeill had helped the original group coalesce, had energized them, set an example, then left for the promised land. But now he was lost, having run into a wall in his attempt to find the true way in the land of Zen. Bob Hense too had had a horrible experience with Japanese Zen. After being thrown out of Sekiunin with McNeill, he found he didn't get along with Ruth Fuller Sasaki in Kyoto either. She was too domineering for him.

They had gone to Japan seeking the true way. They had in mind the satori stories from Paul Reps’s Zen Flesh, Zen Bones, and the ideal settings presented by D. T. Suzuki. What they had encountered was more like an obstacle course—an impenetrable language barrier, endless reprimands that they couldn't understand, no way to read the ritual chants, hours of painful seiza, sitting on the shins, almost no emphasis on zazen, nothing at all that was relevant or nourishing.

[206]

The host temple was utterly unprepared to adapt to foreigners, and these foreigners weren't willing to make the considerable effort necessary to continue under those circumstances.✽ There were a few back then willing to make the necessary effort. Dan Welch spent a year and a half in Ryutakuji—around '63 and '64. It was tough and he toughed it out.

It was March of 1961, and McNeill and Hense were back in San Francisco. McNeill was making an art film. He didn't come around to sit anymore, didn't want to be a monk or study Zen. He said he had discovered his true identity as an artist and homosexual. "I don't want any part of Japanese Zen," he would say. He would still drop by Sokoji occasionally to say hello to Suzuki, and now and then they would bump into each other in Japantown. Sometimes Suzuki would bring a student along and visit McNeill and his Japanese lover at their apartment.

Hense resumed sitting at Sokoji. He realized that it was the only place in the world where he wanted to study Zen, and Suzuki was the only Zen priest he wanted to study with. But he was sad, like an injured soldier home from war. He never wore his robes. Most people didn't even know that he and McNeill had been ordained.

There were a dozen or so regulars at Sokoji, and they sat in order of seniority. Hense was now in the front seat on the men's side, with Bill Kwong and Phillip Wilson. Della, Betty, and Jean were still the three loyal ladies in the first seats on their side.

Then, in late spring of 1961, two newcomers came to Sokoji who would alter the character of Suzuki's group and the course of his life. The first of these was an Englishman in his mid-twenties named Grahame Petchey.

ALAN WATTS was giving one of his freewheeling talks at the Berkeley Buddhist Church on a Tuesday evening in May, piecing together Zen, Taoism, psychoanalysis, and Christian mysticism into a fascinating mosaic. Attending the lecture were Watts and Suzuki's colleague Wako Kato, a man named Iru Price, and a formally dressed young couple, Grahame and Pauline Petchey. Over refreshments, Price presented his card, listing numerous positions and ordinations with Buddhist groups in Malaysia, Thailand, Japan, and America.

On a Tuesday evening in May, at the Berkeley Buddhist Church, Iru Price was giving a talk linking the ancient Buddhist scripture of the Pali Canon to the faith-oriented practice of Jodo Shinshu, the Japanese sect housed in the Buddhist Churches of America. Attending the lecture were Kazumitsu Kato and a formally dressed young couple, Grahame and Pauline Petchey. The Petcheys were pleased with all the thought-provoking nourishment they were discovering in the San Francisco Bay Area. They had recently heard Alan Watts give one of his freewheeling talks piecing together Zen, Taoism, psychoanalysis, and Christian mysticism into a fascinating mosaic. Over refreshments, Iru Price, who wore a toupee, presented his card, listing numerous positions and ordinations with Buddhist groups in Malaysia, Thailand, Japan, and America.

[207]

The Petcheys had recently arrived from Europe. Grahame had already secured a job working as a chemist and was looking forward to finding a Zen master and a sangha, a community of practicing Buddhists, in the Bay Area. Price told him he had to meet Suzuki Sensei at once. Kato pulled out a business card and wrote Suzuki's name and address on the back.

Grahame had grown up in England. His father had been in the Palace Coldstream Guards, the elite corps that protects the royal family, surrounding them with solemn ceremony. From an early age Grahame had wanted to know what life was all about, a query that gave impetus to his religious quest. Grahame called it his nagging question. He first sought an answer from the Church of England. When that didn't satisfy him, he entered a Roman Catholic Carmelite monastery as a layman. There he found monks working on their own nagging questions with an admirable humility, but he left because he couldn't share their beliefs. He went to Rome to get closer to the source, but found only superficiality and hypocrisy.

In Rome he met Pauline, a young French artist who told exciting stories of her family helping downed fliers during the war. Pauline's mother was a U.S. citizen and a Theosophist. In her Paris library Grahame discovered Hinduism, Buddhism, and zazen, the meditation of Zen monks. Pauline had met D. T. Suzuki and Krishnamurti as a teenager. Before long Grahame and Pauline were married and on their way to San Francisco, carrying a large Buddha statue her mother had given them. Grahame's focus from the first had been on trying to figure out what monks did rather than what they were thinking. He tried to do zazen in a chair for a month on the freighter that brought them through the Panama Canal to northern California in early May of 1961. Only a week after arriving, he was on his way to meet the man he hoped would be a master of zazen.

Grahame called to make an appointment, and Suzuki suggested he come to zazen at six in the evening. Grahame came at the appointed time, went upstairs and was chagrined to see on a posted schedule that evening zazen began at five-thirty. He abhorred arriving

[208]

late for his first visit to the temple, his upbringing cried out against it, but the master himself had given him the wrong time—an awkward situation.

The door to the office was open, so he went in to wait. Sitting by himself in a chair, between the streetside din and the office silence, he listened intently to the sounds emanating from the adjacent room—heavy breathing, after a while soft footsteps, and then wham! wham! How surprising! Someone must have dropped something. Then he heard it again. What was going on? Next came bells, chanting, and thumping. He straightened his tie and pulled at his pressed white cuffs.

Finally, the door to the zendo opened and Shunryu Suzuki entered. Grahame stood up but Suzuki paid him no mind. He stood by the door and bowed to each of his students as they exited. Grahame was shocked at their appearance. Rather than the uniform cotton robes of the Carmelites, or the suits, starched collars, and dresses of the London Buddhists, the outfits of the ten or so meditators who slowly filed out, stopping briefly to bow with Suzuki, were blue jeans and sweatshirts. But Suzuki looked right, in his beautiful brown robes. He had a wise face that radiated kindness as well as strictness.

After everyone else had gone, Suzuki sat down with Grahame, served him tea, and talked to him for half an hour. Suzuki asked if he knew how to sit zazen. Grahame said he had tried it in a chair, to which Suzuki responded that it would be better on the tatami. Could he do it? Grahame said he didn't know, but he'd try. That first dayHe followed Suzuki into the zendo where he made it through thirty minutes sitting cross-legged, upright, and still as a palace guard. He had never sat that long at one time before. Christmas Humphreys , founder of the London BuddhistsBuddhist Society, warned that it was dangerous to do more than ten minutes of meditation without adequate training or experienced guidance.

"You take the sitting position very well," Suzuki told him. "You have no problem." That pleased Grahame. Then Suzuki asked, "Can you come back at 5:45 tomorrow morning?"

"I'm a married man,man!" Grahame responded with shock. Married and employed.“Married and employed!”

[209]

He couldn't imagine getting up to go to a temple that early with a day's work ahead. While he pondered, Suzuki offered him more tea. Somehow Grahame picked up on the Japanese custom of offering more tea when it's time to leave. He begged off, and said goodbye.Despite his initial reaction, Grahame decided to come back the next morning. The zazen as Suzuki had explained it made total sense to him. All he had to do was face the wall and follow his breath—no faith, nothing to hold on to, just the nagging question to solve for himself under the guidance of this marvelous, dignified little man.

He went home that first evening filled with an overwhelming joy and told Pauline of his good fortune. He dedicated his whole life to zazen on the spot. Grahame went every morning, every evening, every Sunday, to every lecture. He never stopped. And he asked no questions. To Suzuki he was like a good Japanese student. He liked the way Grahame would brush his feet off in the aisle before he swung around on his zafu to sit facing the wall.

Buddha was great because people were great. When people are not ready, there will be no Buddha. I don't expect every one of you to be a great teacher, but we must have eyes to see that which is good and that which is not so good. This kind of mind will be acquired by practice.

The second propitious arrival of 1961 was a dynamic twenty-five-year-old East Coast transplant named Richard Baker. His studies of Western and Eastern philosophy, art, and poetry at Harvard, in Greenwich Village, and in North Beach had brought him into contact with extraordinary minds, but he had yet to meet an exemplar he could respect and trust. That all changed the evening he went with a friend to Fields Metaphysical Bookstore on Polk Street in San Francisco. Richard and his friend had just come from a Japanese restaurant and were on their way to see a samurai movie. Clowning around in the store, Richard swung an air sword and emitted a

[210]

loud shout, imitating a samurai. George Fields laughed and told him he should go to Sokoji for the lecture by Shunryu Suzuki.

"You should meet Suzuki Sensei," Fields said. "He is a Zen master of the other kind of Zen. He's a wonderful person." By "the other kind of Zen," Fields meant Soto as opposed to Rinzai, which until then had been the focus of almost all the writing in English.

Sitting in a metal folding chair in Sokoji's zendo, Richard was transfixed by Suzuki. It was as if one of the great Chinese masters from the books he'd read had come alive. It wasn't so much what Suzuki said as the unity of his speech and being. Here was a man of deep thought in the classical sense, who knew that thought had its limits and strove for a goal beyond thought.

Later Richard attended a seminar held by Alan Watts and Charlotte Selver, a German woman who taught sensory awareness. Richard already knew Watts and was especially delighted to meet Selver. When Selver left town, he sought out Suzuki again. Though Richard had been to a couple of Suzuki's lectures, he realized for the first time that there was some sort of community around Suzuki. He was definitely interested in this master but thought he himself wasn't up to the meditation.

Later, as he thumbed through a book by D. T. Suzuki (who almost never mentioned zazen), a sentence reached out and grabbed Richard. "To think you are not good enough to practice zazen is a form of vanity." He decided to start going to zazen immediately "in order to stop the wandering of my mind."in order to stop the wandering of his mind.

Richard Baker's mother wrote poetry and his father was a professor who had taught at Harvard and later at the University of Pittsburgh while Richard went to high school. They were not wealthy but spent each summer at his maternal grandmother's home in Maine, Richard's birthplace, where he felt his roots were. He was always a loner and a reader. At Harvard he was called "The Outsider" and "El Darko." During his fourth year at college, he attended lectures by the theologian Paul Tillich, the orientalist John K. Fairbank, and the former ambassador to Japan Edwin O. Reischauer. Despite the impressive qualifications of his teachers, Richard felt

[211]

dissatisfied with what he was learning. He dropped out shortly before graduation to live in New York City until he was twenty-four. Then he went west on a bus to San Francisco in the fall of 1960 with thirty-five dollars in his pocket. On the first day he found poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti's City Lights bookstore and was soon immersed in the literary and artistic circles of North Beach. He moved into an apartment rented by Don Allen, an editor of the Beats he’d come to knowthe prominent editor of The New American Poetry, he’d come to know Allen back East while working at Grove Press. He got a job with a book distributor, and kept looking for something. He fantasized about meeting a Zen master in neighboring Chinatown. Instead, nine months later, he met a Japanese one.

As soon as Richard started to sit regularly he recognized in Grahame Petchey someone who exemplified the excellence a student could demand of himself. Grahame thought they could, in their own way, be like Suzuki, could know what he knew, and could become Zen masters. The way Grahame applied himself, one hundred percent, was just what Richard believed in.

The two became close friends right away. Richard and Grahame were both tall, thin, well-educated, and serious, but there were differences. Grahame had a much easier time with the physical demands of zazen. He could sit up straight in full lotus for the whole forty-minute zazen period without moving. It was actually even longer than that, because one had to be sitting before the period started. Zazen was painful and uncomfortable for Richard. For a long time he couldn't sit even in half lotus. He called his posture "half lily"—perched on several cushions with more cushions under his knees. He had to move at times, but he set goals for himself, such as not moving until Suzuki had finished going around with the stick, halfway through the period.

Grahame brought his life to zazen, single-mindedly focusing on practice in the zendo. Richard brought zazen to his life, making the world his monastery. He watched his breath while driving, concentrated on his feet while walking, and read Buddhist books voraciously. Suzuki said that Grahame concentrated on the posture and Richard on the idea of Zen.

Not long after he came to Zen CenterSokoji, Richard met Virginia

[212]

Brackett, a student at the Art Institute. In May 1962 Suzuki marriedperformed a marriage ceremony for them. The Bakers and the Petcheys were close, and their lives had many parallels, the Petcheys tending to be a step ahead. They both drove Volkswagens, went to samurai movies, had tatami in their apartments, and soon were having babies.

One day Grahame and Richard were in the backseat of a car, with Suzuki riding in front. Richard leaned forward and asked, "Suzuki Sensei, do you think we can understand Buddhism?"

"Yes, if you practice. If you know how to practice," Suzuki replied, turning around and looking Richard in the eyes.

At that moment Richard knew he would practice Zen his whole life.

If

you want to practice zazen, it is necessary to have good friends.

Then naturally you will have good practice.

Suzuki's daughter, Yasuko, and her younger brother, Hoitsu, watched the Montana Maru slowly pull out of Yokohama harbor. On board were Mitsu and Otohiro, off to America. Otohiro cried hard and waved goodbye from the deck.

George Hagiwara, Suzuki's good friend in the Sokoji congregation, had set the move in motion late in 1960. Hagiwara was visiting relatives in Japan, and, at Suzuki's urging, he made a special trip to Yaizu to implore Mitsu to go to America. He told her that Suzuki wanted to stay longer than originally planned. So many people were coming to study with him that he felt he couldn't accomplish his mission in just three years. He needed her help.

Kinu Obaa-san also urged Mitsu to go, saying that Shunryu had been living abroad for two years alone, managing everything by himself. It was important work, and she wanted him to succeed. Mitsu succumbed to the pressure, swallowed her pride, and agreed to go.

[213]

Obaa-san insisted that Suzuki's youngest son go too. Otohiro was seventeen, almost through high school, and she couldn't be responsible for him anymore. Knowing that he might not be back for a long time, Otohiro visited his sister Omi at the mental institution to say goodbye. She had been there for six years. It would probably be her permanent home. He had come only a few times through the years, and she was happy to see him. She had gained a lot of weight.

Once Mitsu had agreed to go, Suzuki wrote to her, "I've bought you a bed with the very best mattress. Also, I got you an American ironing board and fancy new iron. They stand up here to do their ironing. These are the only things I have bought you. It's not much, I know. But I am eagerly awaiting your arrival with Otohiro, whom I also miss very much."

On June 14, 1961, Mitsu and Otohiro were met by Suzuki and a small entourage from the congregation at Pier 41 in San Francisco. Like Suzuki when he'd first arrived, Mitsu and Otohiro were amazed with the opulence and magnitude of the city—and shocked at the austerity of their living quarters. The rooms were clean, but there was only space enough to sleep. Otohiro slept in the attic chamber across the landing from his parents' room. Suzuki had squeezed Mitsu's new bed next to his own. Later sheShe confided to a student that he did not invite her to his bed for six months. She felt that this was because he had been so affected by the attentions of other women.

It wasn't just the urgings of Obaa-san and Hagiwara that had changed Mitsu's mind. In his recent letters Suzuki had told her how kindly some of the women students were treating him. He hinted that advances had been made, though not from his close women students. It would be easier to resist them if she were there, he wrote. One woman had hidden in the building and approached him after he'd locked up. She wouldn't leave, and he finally had to call a senior student to come help him.

There was a very helpful woman named Alice who sometimes cooked for Suzuki and urged him to try a health food diet that

[214]

included carrot juice. She noticed that his teeth were bad, took up a collection, and took him to a dentist to get a set of false teeth. She did his laundry and bought him some long johns. He’d never seen long underwear. He liked them and would continue to wear them to bed and even under his robes when it was cold. She didn't go to zazen much but became a fixture in the kitchen, drinking tea with Suzuki and his students and saying, "Please, Sensei, tell me about Zen. I'm really trying hard to understand." As soon as Mitsu arrived, Alice disappeared and went to India to look for another guru.

The congregation and the zazen students welcomed the new Suzukis. They brought gifts and showed them around town. A Sokoji couple, the Katsuyamas, invited them to dinner on a Tuesday night, and soon it became an established custom. Suzuki took his wife and son to Mimatsu, a cheap, old-fashioned Japanese restaurant with high wooden booths, where he frequently went. Three members of the Sokoji congregation owned it. He showed them Honnami's fine handicraft store and a Japanese confectionery, where they ate green manju sweets and drank tea. George Hagiwara took them all to the Japanese Tea Garden. It was almost as if Mitsu and Otohiro had gone to another Japanese city.

Otohiro was painfully shy and felt lost. He dreaded finishing high school in America and begged not to be made to go. Maybe he could get a job, he said. He had never done well in school in Japan, and he didn't know any English. His father said he would learn. The worst part was that he had to be a junior again. Suzuki organized a group for older teenage boys, both Japanese and Japanese-Americans, not just temple members. About twenty-five of them met once a week. Otohiro made some friends. After a few months he moved into a small apartment across the street that Sokoji maintained for guests.

If you live together, there is not much need to speak to each other. You will understand.

[215]

Mitsu and Shunryu had never lived together before, but they quickly adapted to life together. Her responsibility, as she saw it, was to take care of her husband first, then the members, the zazen students, and the building. She was as industrious as he was. On her first morning, after breakfast, she made pickles while her husband melted down old candles into new ones. She cooked, cleaned, did laundry, received visitors, and met with the women's group. Beyond the call of duty, she sat zazen with her husband's students, taking the front seat next to the kitchen door on the women's side. She enlivened Sokoji. There was a lot more talk with her around. And she was no pushover for Suzuki. They were old friends, and he was used to relating to her on a fairly equal basis, considering the traditional culture they came from. Sometimes students would hear them get into squabbles—a new side to their master!

Mitsu took to her new life at Sokoji with admirable ease. She said it was just like her job in Japan, where there had always been people visiting and hanging out at the school, except now there were Caucasians as well as Japanese. She started to pick up English right away—just enough. With her outgoing personality it was probably easier for her to move into the role of temple wife in San Francisco than it would have been in Japan.

Everybody took to calling Mitsu Okusan, which means "Mrs."—a traditional address for the wife of the house. A lot of people thought it was her name. Okusan was friendly with the zazen students and especially got along with Betty, Della, and Jean. But she objected to the fact that many of the younger ones were often unkempt and had dirty feet.

"Don't complain," Suzuki told her. "They are good Zen students and you should respect them. In fact, you should wash their feet."

Okusan took him seriously and started to put out carefully folded damp towels at the doorway to the zendo. She would show the students how to wipe their feet before they stepped on the tatamiinto the room.

"Clean feet, clean feet," she would say in her sweet, musical voice.

The students accepted her right away, and feet were cleaner.

[216]

More and more we created a feeling of sangha.

At a Saturday afternoon meeting in the spring of 1961 Shunryu Suzuki suggested that his zazen students form a nonprofit corporation so the contributions some of them were making could be deducted from their income tax. Suzuki was meticulous about not using Sokoji's funds for personal use, and he was likewise careful not to confuse the finances of the two congregations. He insisted, for instance, that the zazen students pay rent to the Japanese congregation for their use of the zendo. He felt uncomfortable taking money personally and wanted there to be a treasurer to handle it. After two years of practicing together, it was time to have an organization.

Bishop Reirin Yamada, the new abbot of Zenshuji in L.A. and now the titular head of Soto Zen in America, agreed that the group should incorporate and suggested a Japanese name. Hense said that a Japanese name would not sit well with English-speaking students and suggested the name Zen Center. Everyone liked it. They tossed the name around—a center for Zen, Zen in the center, center yourself on Zen.

In August 1961 Bob Hense was elected the first president, and he started to work on getting Zen Center incorporated. One Saturday he came to Sokoji for a meeting, leaving all the paperwork in his briefcase on a table in the downstairs office. A boy passing by walked in the open door, grabbed the briefcase, and ran off toward Fillmore Street. Hense couldn't catch him. There were no copies of the papers.

All the while Hense was going through intense difficulties, questioning whether he should continue practicing at Sokoji. He poured his heart out to Phillip Wilson one day at Phillip's apartment.

[217]

He said that Suzuki wanted him to be a priest, but that he couldn't give up his architecture practice and his lay life. He said the East couldn't meet the West, that Jung was as close as they could get. "I can't do it anymore," he said. A few days later Hense had a mental breakdown and had to be hospitalized. It was a crisis for the group as well as for him.

A meeting was held, and Grahame Petchey was elected president, even though he'd been there for only twoa few months. Jean Ross, the most outspoken of the old-timers and the obvious choice to succeed Hense, was planning to leave at some point for Japan to study Zen. She nominated Grahame. He proved to be as efficient and thorough as expected. Six weeks later he submitted incorporation papers to the California secretary of state.

Some people felt uncomfortable with the new institutional status. Phillip said they should just sit and not worry about the details—if they lost Sokoji they could sit in a garage. Suzuki wanted to have an established group that did business in a conventional manner. The religion was unconventional enough. He saw practical benefits in a clearly defined organization, and he didn't share his young students' anti-establishment attitudes. Healthy institutions were part of a strong society, he believed, and there was no need to fear that the group would lose its character. He said there would be problems no matter what they did, and that if they concentrated on zazen, on confidence in their buddha nature, they would be all right.

Not that Suzuki himself was a good fiscal manager. Soon after Mitsu arrived, the treasurer of the congregation told her that her husband hadn't been cashing his paychecks. First the treasurer had to explain what checks were; there was no such thing in Japan. She caught on quickly. After some searching, Okusan found the checks when they fell out of a book in the office. From then on they went to her. What had he been living on, she wondered?

Another example of her husband's impracticality led Okusan to insist that she do the grocery shopping. He would sometimes drop by the market on his way home to purchase vegetables, especially

[218]

his favorite, sweet potatoes. The problem was that he would choose the oldest, most wilted and damaged vegetables. She would ask how in the world he could pay money for such produce. He'd say he felt sorry for them. She had even found him on the street picking up Chinese cabbage that had fallen off of the delivery truck—echoes of his father.

With Okusan there, time with Suzuki became more precious. He wasn't as available as before to go out to movies and dinner, although the pleasant morning teatime continued after service, and people still dropped by to say hello or ask questions. Even though Okusan was friendly and enjoyed being with the students, she was always encouraging her husband to go back to Japan. She thought he was too weak and prone to illness to stay.

Suzuki would make his students nervous when he'd mention the possibility of going back. His three-year term would be up the following spring. People felt it was wonderful being with him, but there was a tinge of fear, because they didn't know when it would end. There was a shared enthusiasm to enjoy it while it lasted, make the most of it, learn what could be learned. Amidst the insecurity, there was a sense of certainty that what they were doing together was deeply meaningful and beneficial.

Every once in a while Shunryu Suzuki would do something extreme to dislodge his students from ruts they were in, to knock them off their self-satisfied perches, out of their dreamy lives, and back into the arena of insecurity, where they could rededicate themselves to what he called "beginner's practice." One morning, in the midst of the collective and individual harmony that had accrued from their efforts in zazen and practice, when the confidence level was at its zenith, Suzuki made his morning greeting, walking in gassho around the room behind his students seated on their zafus. He bowed at the altar and assumed his position on the platform facing the room, just as he did every day. In the middle of the period he got up, straightened a few postures, and hit sleepy Bill Kwong on the shoulders, twice each—just as he did every day. He went back to

[219]

his seat and resumed sitting. Then all of a sudden, from Suzuki's small frame roared out the guttural sound of an angry lion.

"You think you're sitting zazen! You're not sitting zazen! You're wasting your time!" He hopped off his cushion and flew down the aisles, whacking each person four times, twice on each shoulder, quick as lightning, his robes flying back, creating a tornado in the zendo. Then he was back in his seat in silence, the room of stunned sitters electrified.

As each bowed to Suzuki at the door on their way out after service, they were a little less sure of themselves. He looked at them squarely but without a hint of anger, as if everything were normal. Complacency and pride lay shattered on the floor. Using the stick like this is a traditional practice of Japanese Zen called rensaku. Suzuki would do it from time to time, often without saying a word.

I think our teaching is very good—very, very good. But if we become too arrogant and believe in ourselves too much, we will be lost. There will be no teaching at all, no Buddhism at all. So when we find the joy of our life in our composure and when we don't know what it is, when we don't understand anything, then our mind is very great, very wide. Then our mind is open to everything. To come to this point, we should be relieved of the arrogance of too much belief in ourselves, and of the kind of selfish, immature, childish mind that is always expecting something. Our mind should be big enough to know, before we know something. We should be grateful before we have something. Without anything, we should be very happy. Before we attain enlightenment, we should be happy to practice our way—or else, we cannot attain anything in its true sense.

First thought, best thought.

Hense was never the same after his nervous breakdown. One day he dropped by Sokoji and bid his teacher of two-and-a-half

[220]

years farewell. He was moving to Chicago to work for an architecture firm. Suzuki shared Hense's sense of failure, but knowing there was nothing he could say to keep him, he let Hense go as gracefully as he'd welcomed him the first day.

Hense had suggested developing a mailing list. Some students wanted to have a way to get the word out that Suzuki was teaching Zen at Sokoji. Thus, the idea of a newsletter was born. Phillip Wilson and his petite scholar wife, J.J., drafted the first one, but wondered what to call it. Zen Center Newsletter? Various names were suggested.

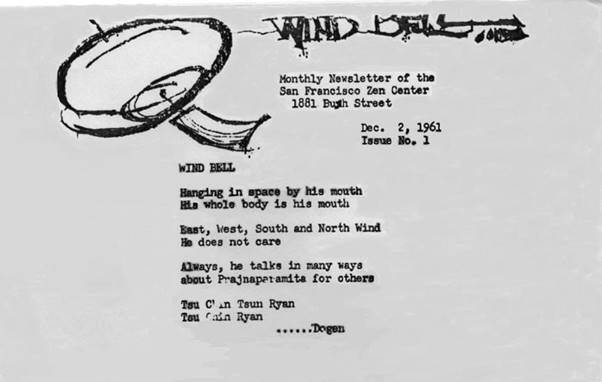

"I'll name it," said Suzuki, and he went upstairs. Twenty minutes later he came down with a piece of paper. The words "Wind Bell" were written on it with a brush in black sumi ink, beside a drawing of the same. Below the drawing was his translation of Dogen's poem "Wind Bell."Wind Bell.

Phillip and J.J. tried to run off the newsletter on the mimeograph machine, but the results were too faint. Suzuki joined them in his work pants and undershirt. He used the ink much more liberally. He was excited. These would be his group's first printed words. He made a mess, spilling the ink on himself and the floor. Soon his arms and torso were covered in purpleink, and he proudly held the first dripping copy.

"I guess I was being too cautious," said J.J., as they cleaned everything up.

The next day was Saturday, December 2, 1961. People stood around reading the newly printed and smudged Wind Bells or tucking them into their pockets. Some took a bunch to post on bulletin boards of colleges and coffeehouses. "What the devil do we need a newspaper for?" Grahame wanted to know. Richard shrugged. "Those people interested in Zen Buddhism may be glad to know that there is a Zen Center in San Francisco which, for nearly two and a half years, has been under the guidance of Roshi Shunryu Suzuki," read Grahame.

[221]

Richard at times used the honorific title roshi for Suzuki. He'd read it, heard Suzuki use it when referring to priests he revered, and according to some people who'd studied Zen in Japan, it was the proper way to address Zen masters there.

The second Wind Bell, in January 1962, reported on a visit by Philip Kapleau to Sokoji. He had given a talk on an old Japanese master named Bassui. Afterward he met with students and talked about his nine years of study in Japan with Sogaku Harada-roshi and Harada's heir, Haku’un Yasutani-roshi, renegade Soto teachers who were using koans like Rinzai teachers. Kapleau's wife joined him in answering questions. In Japan they had sat many sesshins, practicing arduous zazen all night long in the cold and the heat, concentrating on koans and pushing themselves with fervor toward attaining kensho—an enlightenment experience. Harada had died, but Yasutani was still going strong. Suzuki sat listening among his spellbound students. It sounded so different from studying with him. Some wanted to go right away to Japan. Maybe they could get enlightened working with Yasutani. Suzuki's way seemed so slow.

At the following Saturday lecture Suzuki emphasized the difference in the two traditional Zen approaches. "Our way is to practice one step at a time, one breath at a time, with no gaining idea."

For the next year there would be a Wind Bell every month, each one a little longer than the last. Thus the record of Suzuki's talks began. He was getting more comfortable with his English, and he had people who were qualified to make his teaching available in print.

Richard and some other students were always writing down my lectures and asking me many questions about them. What I said with my broken English was very different from what I had in my mind, so I had to write down something. In the Wind Bell they didn't get the original talk, but my broken English corrected by someone else, like Richard.

[222]

Richard Baker would go through his notes from Suzuki's lectures, come up with crystallizations of the teaching, go over the text with Suzuki, and submit it to Grahame for publication in Wind Bell.

If you think, "I practice zazen," that is a misunderstanding. Buddha practices zazen, not you. If you think, "I practice zazen," there will be many troubles. If you think, "Buddha practices zazen," there will not be trouble. Whether or not your zazen is painful or full of erroneous ideas, it is still Buddha's activity. There is no way to escape from Buddha's activity. Thus you must accept yourself and devote yourself to yourself, or to Buddha, or to zazen. When you become yourself, zazen becomes zazen, and Zen becomes Zen.

Like the birds I came,

No road under my feet.

A golden-chained gate unlocks itself.

Shunryu Suzuki was all decked out in red robes with a yellow brocade okesakesa and pointy hat. In his hand he carried a white ox-hair whisk. He recited his poem at the door of Sokoji and ceremoniously entered Sokoji as if for the first time. It was May 20, 1962, three days before his third year was up. He wasn't going back to Japan as planned. He was being installed as the abbot of Sokoji in a Mountain Seat Ceremony, shinsanshiki.

In the downstairs auditorium several hundred older Japanese-Americans in suits and ties and Sunday best, not just temple members but guests from the whole Japanese-American community, sat waiting for him to enter. Scattered among them, tending to take seats in the back, were sixty or so mainly younger Americans in various styles of dress. Amidst the ring of high and low bells and the boom of a drum, struck by Richard Baker in the balcony, Suzuki proceeded upstairs to the zendo and kitchen altars to offer incense

[223]

and recite poems. Soon the chime of bells approached and a procession of guest priests, congregation officers, and children from both groups with flowers in their hands entered the auditorium. Following them Suzuki glided up the aisle as smoothly as a bride and stepped up to an ornate altar put together for the occasion. He offered a stick of incense and recited another poem. Next to him stood Bishop Yamada from L.A., who was officiating.

After I lift this one piece of incense, it is

still there.

Although it is still there it is hard to

lift.

Now I offer it to Buddha and burn it with no

hand,

Repaying the benevolence of this temple's

founder,

Successive ancestors and my master Gyokujun

So’on Daiosho✽Daiosho = Great Priest [great priest]

Suzuki then ascended to the Mountain Seat, sitting in a lacquered chair on a platform beside the altar. Finally he was the abbot of Sokoji and had officially received the temple seal. It was his third such installation, after Zounin and Rinsoin. He had made another three-year commitment. People weren't happy about this back in Yaizu. They didn't understand why he hadn't returned. If they had seen his ragtag Western students at the reception, they might have wondered why he'd waste his time on them. But these students would be there for zazen the next morning and the morning after that.

You are like loaves of bread cooking in the oven.

Suzuki still had no particular plan, but he had high hopes for planting dharma seeds in America and for developing a mutually beneficial exchange with Japan. In March 1962 there had been a farewell party for Jean Ross, before she left for Japan. Jean

[224]

was his second student to go to Eiheiji—the first being Nona Ransom. Jean had had her mind set on going to what she called "the source" for quite some time. He knew she would be challenging for Eiheiji, so set in its ways. The experience with McNeill and Hense had made Suzuki more cautious, but he had confidence that Jean would do better than they had. She wasn't naively idealistic. She had a pragmatic doggedness, and Suzuki was convinced that her conservative, sincere style would put her hosts more at ease. She was still coming to Sokoji only three days a week, but she had persevered through a number of weekend sesshins and passed the initiation of the weeklong sesshin in August 1961. That type of tenacity can't be faked.

In May, Wind Bell printed Jean's first letter from Eiheiji. She was working and practicing with the monks. She had her own room and was getting up at 3:00 am to be out of the washroom before they came in at 3:30. She was not complaining about the hours of chanting every day and climbing ninety-five steps daily to Dogen's memorial hall. She was withstanding the culture shock and making friends despite the language barrier.

"These priests from the country are men, not saints. Their faces express a high degree of individualism tempered by much discipline," she wrote. And later, more poignantly, "As for me, I stood on the Eiheiji earth, and for the first time I felt planted in earth. I began to recognize buddha nature not only in man but in all forms of life. Such expansion eased the pressure of adjustment."

The practice of zazen is not for gaining a mystical something.

Zazen is for allowing a clear mind—as clear as a bright autumn sky.

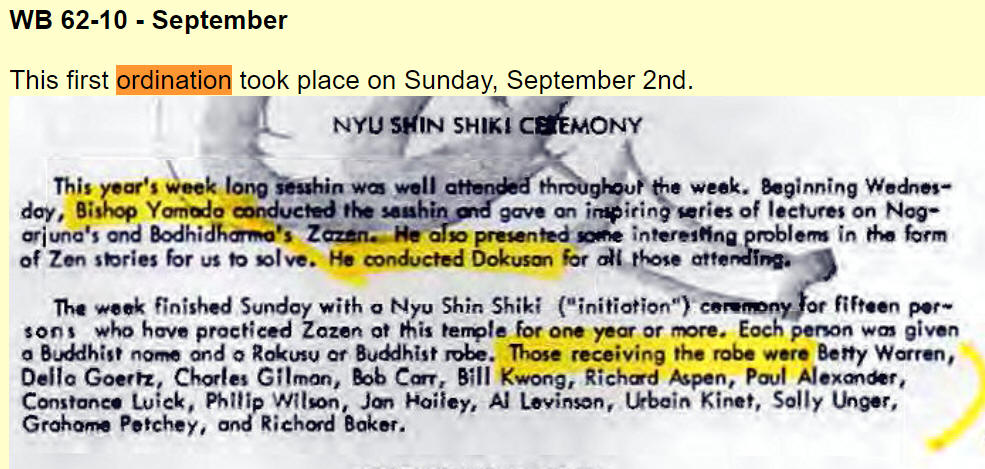

In August 1962 Suzuki and his students had their third annual weeklong sesshin. This one started earlier in the day, ended later, and was the first one to go morning to night for a full seven

[225]

days. Suzuki had invited Bishop Yamada to lead it, and he came up from L.A. for the last five days. Yamada gave lectures on the great Indian sage Nagarjuna and the semi-legendaryChina’s first ancestor, Bodhidharma,✽ Don't see Bodhidharma as legendary anymore thanks to the work of Andy Ferguson and Red Pine. and conducted dokusan, private interviews. Suzuki rang the bells, made sure everything went smoothly, and sat every period—encouraging his students with his steadfastness. The students endured pain in their legs and backs, boredom and restlessness. Thirty people sat at least some of the sesshin and over half as many stayed for the whole thing.

Pauline Petchey had never had anything important to talk to Suzuki about in dokusan. She would ask him theoretical questions like, if a tree falls in the forest and no one hears it, does it make a sound? "It doesn't matter," he'd answered.

Pauline sat the sesshin. Her legs were killing her. It was tough being the wife of the guy who was setting the standard. Grahame never moved, even in the extra-long periods that Suzuki would throw in unexpectedly. Pauline, on the other hand, was just trying to get through the day without screaming. She sat in the middle of the room and so had an aisle in front of her rather than the wall. During a moment of particular difficulty, she saw Suzuki step in front of her. Something about his feet struck her. She watched them intently as he walked slowly by. Then a calm came over her, and the pain separated from her—it didn't matter anymore. Her chattering mind dropped away. Standing for kinhin, she looked around the room as if seeing her fellow students for the first time and realized how trapped they all were in petty social games. She felt love for everyone in the room. She looked at Suzuki and saw him connected with them in this trouble-free space, not in the realm of their delusion.

Soon afterward she saw him in dokusan. After bowing three times to the floorprostrations, she sat on the cushion facing him. After a moment of following breaths together, she told him about her experience, which she was sure signaled permanent enlightenment. "Very nice," he said. "You've reached deep zazen."

[226]

On the last day of the sesshin, at a lay

ordination,✽

students who had practiced with Suzuki for over one year received

precepts and a Buddhist name. Yamada had brought fifteen rakusus, which turned

out to be the perfect number.✽

Those lay ordained received strips like a wide ribbon,that hung around the neck without the center bib that was always used later.

One by one, in order of their arrival at Sokoji,

people came forward to receive their cloth rakusus and lineage papers—the names

of the ancestors dating back to Buddha written on rice paper, folded, and

placed in a rice-paper envelope with calligraphy by Suzuki on the front. Betty

and Della were the first in line (Jean was in Japan). Grahame and Richard were

last, having arrived just over a year before.

students who had practiced with Suzuki for over one year received

precepts and a Buddhist name. Yamada had brought fifteen rakusus, which turned

out to be the perfect number.✽

Those lay ordained received strips like a wide ribbon,that hung around the neck without the center bib that was always used later.

One by one, in order of their arrival at Sokoji,

people came forward to receive their cloth rakusus and lineage papers—the names

of the ancestors dating back to Buddha written on rice paper, folded, and

placed in a rice-paper envelope with calligraphy by Suzuki on the front. Betty

and Della were the first in line (Jean was in Japan). Grahame and Richard were

last, having arrived just over a year before.

It was a happy day for Suzuki, another small step in his effort to establish Buddhism as he knew it in the West. The ceremony was conducted in Japanese, which the students didn't understand, but Suzuki told them they were "making the vow to keep the enlightened life." He explained the meaning of their new Buddhist names. Della would still be called Della, but she was also now Zendotei Jundaishi, a rather long name composed of characters that he said meant, "Zen way, faith, refined naturalness." Before the ordination Della told Suzuki that she had not rejected her Lutheran upbringing. "I guess I'm going to be a Christian Buddhist," she said. "That's all right," Suzuki answered.

Suzuki took the backseat, as he had with Kishizawa at ordinations at his temple in Yaizu. He deferred to the older Yamada because it was proper. He was the bishop. In this way word would get back to Japan that there were some serious students in America. He appreciated the support he got from Yamada, obligatory but still helpful. It was good for his students to see and hear another priest. "I am very grateful we have instruction from various teachers," he said. "We need more teachers."

While the sesshin was in progress a letter had arrived from the secretary of state—Zen Center's nonprofit status was official. They had raised almost five thousand dollars that year and had been able to save over five hundred, which would go into a building fund. The ordination and incorporation were important to Suzuki, but he made clear what was essential for his teaching to take hold.

[227]

Unless you know how to practice zazen, no one can help you. Heavy rain may wash away the small seed when it has not taken root. You should not be like a sesame with no roots, or your practice will be washed away. But if you have a really good root, the heavy rain will help you a lot.

Some people felt like Phillip, who asked why they needed any organization or any ordination ceremony. "It's just like the Catholic Church," he said. Little did he realize how close he was to the truth. Soto Zen was full of hierarchy and ceremony in Japan, but consideringJapan. Considering the autonomy of individual temples and priests, and the growing role of the membership in making decisions, maybe the Baptist Church would have provided a better analogy.

Suzuki had to show them how these things were done in Japan, he said, because that's what he knew. He had to establish Zen Center in a way that he was comfortable with. Being impatient would not work. Someday they would have their own Buddhist forms. “Transmitting Buddhism to America isn't so simple. You can have your own way someday, but first learn mine. And don't be in too big a hurry. It's not like passing a football.”

Transmitting Buddhism to America isn't so simple. You can have your own way someday, but first learn mine. And don't be in too big a hurry. It's not like passing a football.

A brief audio excerpt from a Shunryu Suzuki lecture as in the audiobook.

| Bowing | Journeys |