What Kind of Buddhist was Steve Jobs, Really?

[Originally posted on NeuroTribes on Oct 28, 2011] - Link (copied here on cuke in case it disappears from there)

One reason I was looking forward to reading Walter Isaacson’s new biography of Steve Jobs was my hope that, as a sharp-eyed reporter, Isaacson would probe to the heart of what one of the few entrepreneurs who really deserved the term “visionary” learned from Buddhism.

By now, everyone knows the stories of how the future founder of Apple dropped acid, went to India on a quest for spiritual insight, met a laughing Hindu holy man who took a straight razor to his unkempt hair, and was married in a Zen ceremony to Laurene Powell in 1991. I was curious how Jobs’ 20-year friendship with the monk who performed his wedding — a wiry, swarthily handsome Japanese priest named Kobun Chino Otogawa — informed his ambitious vision for Apple, beyond his acquiring a lifetime supply of black, Zen-ish Issey Miyake turtlenecks.

Isaacson does a fine job of showing how Jobs’ engagement with Buddhism was more than just a lotus-scented footnote to a brilliant Silicon Valley career. As a young seeker in the ’70s, Jobs didn’t just dabble in Zen, appropriating its elliptical aesthetic as a kind of exotic cologne. He turns out to have been a serious, diligent practitioner who undertook lengthy meditation retreats at Tassajara✽ Steve Jobs didn't do retreats at Tassajara as his biography reports. He went in with Daniel Kottke once a year for a few times to go to the baths, walk around, get some bread, and drive out. They thought of it as a pilgrimage. But he did have a long term and serious relationship with Kobun Chino and Less Kaye, abbot of Kannon Do in Mountain View. Kobun said Jobs couldn't sit more than an hour at a time. There's a chapter on Jobs and Zen in part three of the yet unpublished Tassajara Stories. Maybe I should get it published in a magazine. - dc — the first Zen monastery in America, located at the end of a twisting dirt road in the mountains above Carmel — spending weeks on end “facing the wall,” as Zen students say, to observe the activity of his own mind.

Why would a former phone phreak who perseverated over the design of motherboards be interested in doing that? Using the mind to watch the mind, and ultimately to change how the mind works, is known in cognitive psychology as metacognition. Beneath the poetic cultural trappings of Buddhism, what intensive meditation offers to long-term practitioners is a kind of metacognitive hack of the human operating system (a metaphor that probably crossed Jobs’ mind at some point.) Sitting zazen offered Jobs a practical technique for upgrading the motherboard in his head.

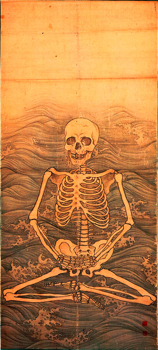

The classic Buddhist image of this hack is that thoughts are like clouds passing through a spacious blue sky. All your life, you’ve been convinced that this succession of clouds comprises a stable, enduring identity — a “self.” But Buddhists believe this self this is an illusion that causes unnecessary suffering as you inevitably face change, loss, disease, old age, and death. One aim of practice is to reveal the gaps or discontinuities — the glimpses of blue sky — between the thoughts, so you’re not so taken in by the illusion, but instead learn to identify with the panoramic awareness in which the clouds arise and disappear.

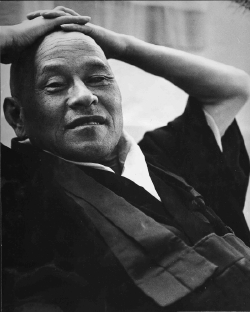

One of the books that inspired Jobs to become interested in this process was Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism by Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, a Tibetan lama who led a group of monks over the Himalayas in the 1950s to escape the invading Chinese army. Isaacson doesn’t do much more with Trungpa than name-check the title of his book, but he was a fascinating and controversial figure in his own right. After being recognized as the reincarnation of a great lama as a boy, Trungpa fled his home country and went to the British Isles, eventually graduating from Oxford. He began teaching in the traditional style at a meditation center in Scotland, complete with maroon robes, a shaved head, and vows of celibacy and sobriety; one of his early students went on to become the chameleonic pop star David Bowie.

After a nearly fatal car crash — driving into a joke shop after being distracted by a billboard, no less — Trungpa scrapped his old approach to teaching. He realized that the trappings of being a Tibetan lama were an unnecessary barrier to reaching the widest possible audience for Buddha’s revolutionary message. He jettisoned the robes, grew out his hair, eloped with the brilliant teenage daughter of a high-born British family, and emigrated to America, where he soon found legions of hippies who had reached the limits of psychedelic insight and were eager for teachings on the nature of mind from a deep-rooted contemplative tradition.

Trungpa became a hugely popular and influential teacher, praised (rightly) for his brilliant exposition of esoteric concepts in fresh, unsentimental, idiomatic English; and fiercely criticized (also rightly) for his heavy drinking and flamboyant womanizing. From his home base in Boulder, where he established a contemplative university called Naropa, Trungpa became the spiritual advisor to many counterculture luminaries, including poet Allen Ginsberg, author Ken Wilber, and singer/songwriter Joni Mitchell, who portrayed him (accurately) in a song on her haunting Hejira album called “Refuge of the Roads.”

I suspect that one of the things that Jobs found inspiring about Trungpa’s writing — beyond its bracingly direct tone and surgical deconstruction of the lies that prevent us from seeing things as they are — was his profound respect for artists, poets, and musicians, whom he saw as fellow warriors against delusion (which he called “neurosis,” adopting the lexicon of Western psychology.) This passage of Trungpa’s, from an essay on “dharma art,” could have been a blueprint for Jobs’ uncompromising vision for Apple:

Our attitude and integrity as artists are very important. We need to encourage and nourish the notion that we are not going to yield to the neurotic world. Inch by inch, step-by-step, our effort should wake people up through the world of art rather than please everyone and go along with the current. It might be painful for your clients or your audience to take the splinter out of their system, so to speak. It probably will be quite painful for them to accommodate such pressure coming from the artist’s vision. However, that should be done, and it is necessary. Otherwise, the world will go downhill, and the artist will go downhill also.

Another influence on Apple’s young founder was the book Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind by Shunryu Suzuki-roshi, the founding teacher of San Francisco Zen Center. Assembled from Suzuki’s lectures by a young student named Trudy Dixon who died of cancer while the book was in production, it’s a graceful, welcoming, insightful guide to the spirit of Zen practice. Suzuki’s playful language — like the voice of a wise child — communicates profound and subtle insights about what Zen teachers call the Great Matter of life and death, dancing gracefully on the edge of the unsayable. It’s one of those rare books that can be read at many points in your life, and it always seems uncannily relevant.

At the same time, it was a subversive piece of work. Swimming against the tide of Zen writings of its era, Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind downplayed the enticing concept of enlightenment in favor of slow, steady mindfulness practice “with no gaining idea” — that is, with no hope that your next session on the cushion would bring about a shattering, life-changing flash of satori. Suzuki-roshi didn’t even claim to be enlightened himself, which was a shocking thing for a renowned Zen teacher to admit at the time (laughingly confirmed by his mischievous wife, Mitsu). You didn’t sit zazen to become a Buddha, Suzuki-roshi used to say: “You’re perfect just as you are — and you could use a little improvement.”

Jobs’ celebrated motto for the original Mac team — “the journey is the reward” — could have been lifted from the pages of Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind. For Suzuki-roshi, the path was the goal.

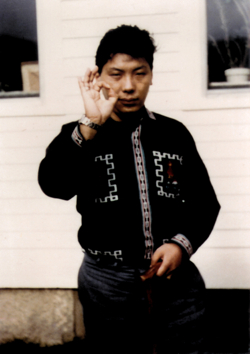

The only regrettable aspect of Isaacson’s account is his clownish portrayal of Jobs’ teacher and friend for two decades, Kobun Chino Otogawa, as a hapless bore who spoke in needlessly cryptic “haiku.”

Isaacson quotes former Apple employee Daniel Kottke, the friend who accompanied Jobs on the India trip, as saying that he found Kobun “amusing” and little more: “Half the time we had no idea what he was going on about. I took the whole thing as a lighthearted interlude.” Describing the Jobs’ wedding ceremony at the Ahwahnee Lodge in Yosemite, Isaacson says the Zen priest “shook a stick, struck a gong, lit incense, and chanted in a mumbling manner that most guests found incomprehensible.”

I’m tempted to blurt out, Yes, Mr. Isaacson — particularly the guests who didn’t understand Japanese, the language of much of the Buddhist liturgy that Jobs had been chanting at Zen centers for two decades. Imagine a description of Yom Kippur in a biography of a major Jewish historical figure that dispenses with the Kol Nidre as “incomprehensible wailing.” Adding to Isaacson’s awkward handling of Jobs’ teacher is his insertion of a comment from an Apple software engineer who “thought [Kobun] was drunk” at the wedding ceremony. Isaacson quickly interjects “he wasn’t” — which makes you wonder why the author felt compelled to include the remark at all.

Issacson loses interest in Kobun after that, leaving out one of the most poignant aspects of his life, which surely also had a profound impact on Jobs. In 2002, Kobun drowned in a shallow, icy pool at his student’s home in Switzerland, trying to save the life of his 5-year-old daughter Maya, who perished anyway. I imagine the loss of his longtime spiritual friend was particularly rough on Apple’s founder when he came face-to-face with his own mortality the following year after his diagnosis of pancreatic cancer.

If it sounds like I have a personal stake in this, I do. In the late ’70s and early ’80s, I was a student at San Francisco Zen Center, where Kobun frequently gave dharma talks. Like Jobs, I meditated at Tassajara, though not as often as he did. I spent most of my own time on the cushion at Zen Center’s headquarters in San Francisco, known informally as City Center, in a former home for single Jewish women designed by the Bay Area architect Julia Morgan.

In fact, when I decided to leave Zen Center because I felt I was too young (20) and unworldly (I’d had only one relationship) to become a monk, it was Kobun who encouraged me to plunge wholeheartedly into secular existence, advising me sensibly, “Your challenge will be to find a way of life that is as meaningful to you as Zen practice.” I eventually found it in writing.

Kobun was similarly encouraging to young Jobs, telling him, in Isaacson’s words, that he “could keep in touch with his spiritual side while running a business.” It’s intriguing, if depressing, to imagine what the digital world would have been like if Kobun had given Jobs the opposite advice, along the lines of Jobs’ own now-infamous challenge to Pepsi CEO John Sculley: “Do you want to sell stylish electronic gadgets for the rest of your life, or come with me and vow to save all sentient beings from suffering?”

Another thing that becomes clear in Issacson’s book is the crucial role of what Buddhists call mindfulness played in securing Apple’s success. When a 15th century poet named Ikkyu was asked, “What is the meaning of Zen?” he replied, “Attention.” Asked to explain further, he replied, “Attention means attention” — one of those cryptic, haiku-like utterances that can make people think you’re drunk. But attention, in Zen practice, means more than just being mindful of your breath in the zendo. It means investing moment-to-moment awareness in everything you do in the course of an ordinary day — whether running for the bus, cooking a pot of rice, talking to your in-laws, taking your blood-pressure pills, or making love.

Or, say, crafting a totally new kind of computer “for the rest of us.” The physical environments Jobs practiced in at Tassajara and other Zen centers offered breathtaking juxtapositions of highly cultivated traditional craftsmanship and wild, rugged California landscapes. I doubt that the Japanese joinery (no nails!) that held up the walls of the zendo was lost on the aspiring design geek, or that he was unmoved by the vibrant, airy layout of Greens Restaurant in San Francisco, punctuated by an enormous, twisting redwood burl (rescued from a beach in Marin) that had been sculpted to sprout tables and chairs. Zen Center’s aesthetic was a harmonious fusion of East and West — as Apple’s would be.

Indeed, the senior teacher at Zen Center who oversaw all this construction — a charismatic Harvard graduate named Richard Baker-roshi — was known as both a supremely articulate exponent of Zen philosophy and a relentless, abrasive micromanager who would putter around the dining room at Greens in his robes, straightening napkins and fussing with flower arrangements on every table. Sound familiar?

Like a Zen fussbudget, Jobs paid precise, meticulous, uncompromising attention to every aspect of the user experience of Apple’s products — from the design of the fonts and icons in the operating system, to the metals used to cast the cases, to the colors on the boxes and in the magazine ads, to the rhyming proportions in the layout of Apple stores. He encouraged mindfulness in his customers too, by designing his computers so superbly that they faded into the background as creative imagination took over. Jobs thought of computers as “bicycles for the mind,” and Isaacson reports that, for one ill-considered month in 1981, Jobs even tried to rechristen the Mac “the Bicycle.” (For once, his team ignored him.) The point was to get where you wanted to go, and eventually the terrain available for exploration included the entire global network. By contrast, Windows machines are like heavy, clunky, training-wheel affairs that are always calling attention to themselves with hectoring dialog boxes and protocols that require hundreds of pages of tedious documentation to explain.

The Mac launched a democratizing revolution — for those who could afford it. And Jobs’ insistence that Apple create products that its customers would already know, intuitively, how to use is what transformed computing from a geeky oligarchy of Usenet wizards into a digital sandbox for the masses.

In his pursuit of intuitive computing, Jobs found a kindred spirit in Jonathan Ive, the sweet, self-effacing young British designer who helped him create the iMac, the iPod, the iPad, the MacBook Air, and the iPhone — all the gadgets that made your jaw drop when you first saw them, because they seemed so elemental, unfussy, and inevitable; as if they were platonic fusions of form and function that were already waiting somewhere in the universe when Ive and Jobs “discovered” them together.

To indulge in a little Buddhist jargon, the best Apple products seem like they suddenly appeared in emptiness (Śūnyatā), unencumbered by previous notions of what a “computer” or “phone” or “MP3 player” or “tablet device” should be. They were cosmically clean; avatars of the new.

One of the most memorable lines in Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind is Suzuki-roshi’s statement, “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, in the expert’s mind there are few.” Suzuki didn’t want his senior students to take a seat on the cushion each morning feeling like Zen adepts who had been there and done that. He wanted them to approach meditation with the open-minded curiosity of an amateur trying it for the first time. Apple devices, you might say, are sophisticated tools for evoking, supporting, and sustaining shoshin, beginner’s mind.

Indeed, Jobs’ commitment to mindfully-crafted excellence extended even to aspects of his products that were invisible. In Jony Ive’s smart and pointed eulogy for his best friend last week, the design chief reminisced about spending “months and months” with Jobs perfecting parts of Apple’s machines that most users would never see (“…with their eyes,” Ive then tellingly added.) “Steve believed that there was a gravity, almost a civic responsibility, to care way beyond any sense of functional imperative.” When Apple introduced one of the first products they designed together — the iMac with its transparent Bondi blue case, a design trope eventually echoed everywhere from kitchen appliances to running shoes — Jobs bragged that the back of the iMac looked better than the front of his competitors’ computers.

That was a lesson Jobs first learned from his adopted father, Paul, a skilled mechanic who told him, “‘You’ve got to make the back of the fence that nobody will see just as good-looking as the front of the fence. Even though nobody will see it, you will know, and that will show that you’re dedicated to making something perfect.”

In monasteries in Japan, the young monks (unsui, or “cloud-water” people) are encouraged to do good deeds for others, but anonymously. The back of your practice is as important as the front.

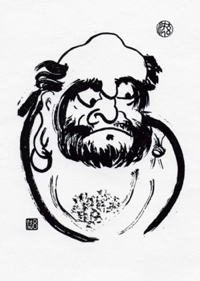

I suspect that Jobs’ chutzpah as the Valley’s most dramatic and effective showman was inspired, at least in part, by the mythical Zen rogues who drank sake, caroused with whores, shunned temples, mocked hollow rituals, sat zazen in caves, and turn out to be the only ones worthy of inheriting the old master’s robe and bowl by the end of the story. Zen flourishes in irreverence, subversion, inscrutability, and self-mockery — all words that describe Jobs’ style but the last.

Undertaking study of the Great Matter is serious business to Zen students, but it must be done with humor and a light touch. In addition to being a meditation teacher, Kobun Chino was a renowned master of kyūdō, Zen archery. He was once invited to give a demonstration of his skills at Esalen, the famed retreat center near Big Sur. Kobun placed his feet in the traditional, grounded ashibumi stance, straighted his spine, drew the bow, and let loose his arrow — which not only missed the target completely, but soared over the fence behind it, plummeting into the Pacific below. The spectators were aghast until they looked up at Kobun, who gleefully shouted, “Bullseye!”

Isaacson is admirably frank about the core tenet of Buddhism that Jobs seems to have bypassed: the importance of treating everyone around you, even perceived enemies, with basic respect and lovingkindness. It’s tempting now to cast Jobs’ tantrums, casual brutality, and constant berating of “shitheads” as the brave refusal to compromise his ideal of perfection — even as a kind of tough love that inspired his employees to transcend their own limitations. But a more skillful practitioner would have tried to find ways to bring out the genius in his employees without humiliating them — and certainly would have found ways of manufacturing products that didn’t cause so much suffering for impoverished workers in other countries. The moment in Isaacson’s book when Jobs tells the Mobile Me team after the project’s disastrous début, “You should hate each other for having let each other down,” shows that even near the end of his life, Jobs had more to learn from his teachers.

I suspect that the most powerful lesson Jobs took from his years with Kobun was to accept death as an inevitable part of life, which served him well when he learned that his own death was imminent. Jobs’ moving commencement speech at Stanford in 2005 was a classic dharma talk, made better by not mentioning Buddha:

Remembering that I’ll be dead soon is the most important tool I’ve ever encountered to help me make the big choices in life. Because almost everything — all external expectations, all pride, all fear of embarrassment or failure – these things just fall away in the face of death, leaving only what is truly important. Remembering that you are going to die is the best way I know to avoid the trap of thinking you have something to lose. You are already naked. There is no reason not to follow your heart…

No one wants to die. Even people who want to go to heaven don’t want to die to get there. And yet death is the destination we all share. No one has ever escaped it. And that is as it should be, because Death is very likely the single best invention of Life. It is Life’s change agent. It clears out the old to make way for the new. Right now the new is you, but someday not too long from now, you will gradually become the old and be cleared away. Sorry to be so dramatic, but it is quite true.

Your time is limited, so don’t waste it living someone else’s life. Don’t be trapped by dogma — which is living with the results of other people’s thinking. Don’t let the noise of others’ opinions drown out your own inner voice. And most important, have the courage to follow your heart and intuition. They somehow already know what you truly want to become. Everything else is secondary.

I would have loved to have asked Jobs himself what he learned from his years of Zen practice — but the one time I tried to do that, during an interview in Cupertino, an anxious PR handler cut me off by saying, “I thought you agreed not to ask Steve any personal questions!”

I’ve never forgotten something else Jobs told me that day: “If you want to know what I think, just look at our products.” At the time, it seemed like a crabby, dismissive, “bad Steve” response. But it was the most Zen thing he could have said.